With forests rapidly losing their capacity to regulate the climate, countries have to urgently step up finance for REDD+ and companies must implement their zero-deforestation commitments. Terry Slavin reports

It’s been 10 years since Erik Solheim, then Norway’s minister of the environment and development, committed to contribute $1bn to Brazil’s newly established Amazon Fund to combat deforestation in the world’s most ecologically important rainforest.

Norway has since poured more than $3bn into the Norwegian Climate and Forest Initiative, working with Brazil, Indonesia, Guyana, Democratic Republic of Congo and other countries to try to reverse the precipitous decline in the world’s rainforests. Its model combines upfront funding for capacity-building in countries with payments based on verified results, something that has since become known as REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation).

It is not difficult to see why Norway, a country of 5 million inhabitants that earned £26bn from North Sea oil last year, would want to offset some of its carbon footprint by investing in forests – particularly after the 2015 Paris Agreement specifically endorsed forests as a climate mitigation strategy, citing scientific evidence that bolstering their role as carbon sinks could get the world around 30% towards the goal of keeping temperature rises under 2C.

We cannot continue to incrementally reduce deforestation. We have perhaps a few years left to get deforestation down

But one thing that was striking at last week’s Oslo Forest Forum, a biannual meeting of the world’s most important forest nations and stakeholders, was how few countries have joined Norway in ponying up hard cash and how urgent the need is for more to join the battle.

As Frances Seymour of World Resources Institute, who was lead organizer of the conference, pointed out in the opening plenary, combating deforestation has attracted less than 2% of climate finance. "We're like a fire brigade trying to put out a fire in a big building with a bucket of water and a teaspoon," she said. "A lot of the constituencies that should be with us seem to be asleep."

WRI’s Global Forest Watch platform revealed its latest data at the conference, showing that tree cover shrank by another 29.4 million hectares in 2017, close to the record 29.7m ha lost in 2016.

The highest tree cover loss was seen in Brazil, where rampant forest fires undermined declining deforestation rates; Colombia, where deforestation shot up 46% as forests amid encroachments by agriculture in the wake of the newly struck peace; and the Democratic Republic of Congo, home to the second-largest tropic tree store after the Amazon, where deforestation set a new record high, driven largely by illegal artisanal and industrial logging.

Dr Carlos Nombre, earth systems and climate scientist from Brazil, told reporters that forests’ CO2 mitigation potential is now under urgent threat. “What science is telling us is that we are running out of time. The forests’ role of taking carbon out of the atmosphere may not be with us in the future if we don’t act immediately. We cannot continue to incrementally reduce deforestation. … We have perhaps a few years left to get deforestation down and commit to major reforestation of tropic forests. It is urgent and it is mandatory that we come up with a new sustainable development pathway for the global tropics.”

Norway’s minister of climate and environment warns that the world’s forests face an existentialist threat

Ola Elvestuen, Norway’s minister of climate and environment, who opened the conference with the warning that the world’s forests face “an existentialist threat”, said in an interview that Norway’s expectations 10 years ago that other countries would follow its lead had been “unrealistically high”.

Some other countries have opened their purse strings, but the list is short: at the conference Norway, Germany and Ecuador signed a $50m partnership to protect 13.6m ha of the Ecuadorean Amazon, the latest disbursement through REDD+ Early Movers, a programme by the German Development Bank to help countries help prepare for REDD+, which has also had substantial UK funding, particularly for Colombia.

The Early Movers programme has made results-based payments to the Brazilian provinces of Acre and Mato Grosso, which in 2017 received R$115m ($30m) and R$117m respectively.

“We have good co-operation with Germany and with the UK,” Elvestuen said. “but we need to bring in more countries on board on the funding side, especially if we can get the countries performing for results-based payments. Then the numbers will be completely different than today.”

The problem is that few forest countries, with the exception of Brazil, have actually seen any finance flow from action to reverse deforestation. Funding so far has mainly gone to help countries prepare for REDD+: to buy monitoring systems, increase NGO and community participation in national planning and policy processes, and safeguard against unintended social and environmental consequences.

It was evident at the conference that much store has been put in the prospect of jurisdictional REDD+ deals with sub-national governments, such as those in Acre and Mato Grosso, and in Indonesia, where some 30 districts now have strategies for “green” growth.

Jurisdictional agreements enable a more holistic approach, focusing on smallholder farmers as well as deforestation

One attraction of jurisdictional REDD+ projects is that having multiple agreements at a more local level reduces the risk of a country-wide programme falling prey to politics when governments change. There was uproar last year, for example, when Michael Temer’s new government in Brazil used money in the Amazon Fund to fill the gaps when it slashed the environment budget by 51%.

But another is that jurisdictional agreements enable partners to take a more holistic, wall-to-wall approach, focusing on improving livelihoods of smallholder farmers at the same time as addressing deforestation.

Crucially, with beef, soy, palm oil and timber products responsible for some 70% of deforestation, they also open up a route for the hundreds of companies that have made zero-deforestation commitments by 2020 to make substantial, verifiable progress.

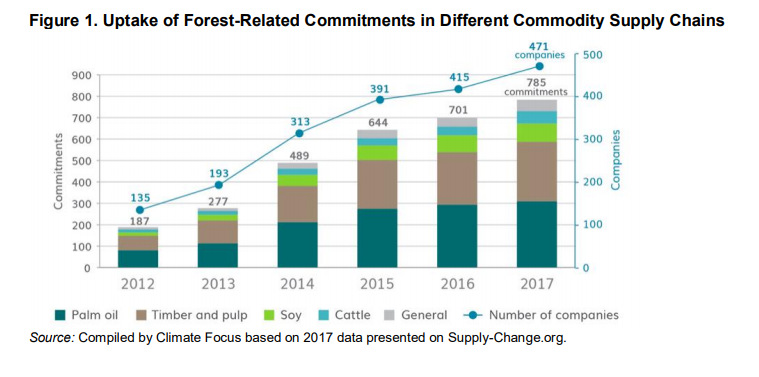

The failure of the vast majority of companies to do anything to implement commitments they made as part of the Consumer Goods Forum, Tropical Forest Alliance 2020 and the New York Declaration on Forests, was underscored in new reports by WRI and Tropical Forest Alliance 2020.

One participant in a workshop emphasised the need for much greater transparency to allow investors to monitor progress on no-deforestation commitments. He pointed to Wilmar, the world's biggest palm oil supplier, which in 2013 earned plaudits for committing its entire operations, including subsidiaries and third-party suppliers, to a ‘no deforestation, no peat, no exploitation’ policy.

Last week Greenpeace issued a report pointing to overlapping management and trading links between Wilmar and Gama Plantation, which Greenpeace accused of having destroyed rainforest twice the size of Paris in Papua since 2013. Earlier this week, Wilmar announced that co-founder Martua Sitorus and its country head for Indonesia had resigned. "We need more of the watchful eye," the participant said.

Marco Albani, director of Tropical Forest Alliance 2020 (TFA 2020), told the workshop that the fact that large areas of tropical forest remain uncovered by corporate commitments of any kind mean it is important for companies to support approaches that cover entire landscapes.

This gap in coverage is most obvious in palm oil. According to TFA 2020’s report, two-thirds of the palm oil market is covered by corporate forest commitments, but in Indonesia and Malaysia, which produce 85% of the world’s palm oil, fewer than one-third of the combined production area is under commitment, mainly because of the prevalence of smallholder farmers.

Unilever’s agreement with district governments in Indonesia’s Central Kalimantan in 2015 to preferentially source zero-deforestation palm oil from local smallholder farmers is a pioneering attempt to plug this gap.

There is a disconnect between a desire of the part of jurisdictions [to tackle deforestation] and any tangible results

Albani said the large volume of corporate commitments had created “the political space for jurisdictional leaders to try to do things differently”. And from the companies’ point of view, jurisdictional approaches provide a “pragmatic entry point, something real that companies and investors can grab with both hands, be a bit bold, go outside of their comfort zones, but do something real”.

In an interview, Seymour of WRI emphasised how important it is for other companies to follow Unilever’s lead, so sub-national governments can see the “value proposition” in addressing deforestation.

“There is a disconnect between a desire of the part of jurisdictions [to tackle deforestation] and any tangible results for doing so on the horizon,” she said.

This point was driven home by Rukka Sombolinggi, secretary general of the Indigenous Peoples Alliance of the Archipelago (Aman) in Indonesia, who presented research showing that 24% of global carbon stock locked up in forests is within indigenous territories, most of which have no recognition or protection.

She told the conference that one of Indonesia's "green" districts, West Papua, which has stopped giving out licences to palm oil concessions and is creating conservation zones preserving forests on indigenous lands, wasn't able to get money to build a micro-hydro scheme for clean electricity.

"Indigenous people, local governments have performed, but where is the money? We are still talking so much at a big level, but we aren't paying attention to what is happening at the local level. There are good things happening at the local level to conserve forests that we need to expedite, because if we don't do it soon, those people will give up."