Indian businesses have had their foot on the growth pedal for a decade or so. Now they are seeing a wider view of their role in society

India’s economic growth has been creeping upward for the past decade or so. In fact, such is the trajectory that the country’s once moribund economy is now the world’s fourth largest in purchasing power parity terms.

For India’s social development, this is a welcome trend. Millions have been lifted out of poverty in recent years: 10 million a year since 2004, if official figures are to be believed.

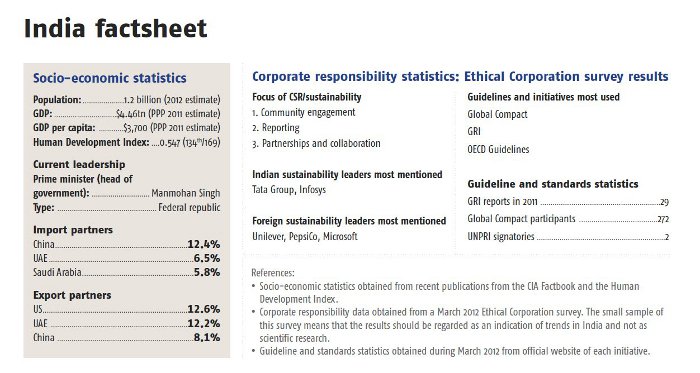

Yet substantial challenges remain. The poor are not only voluminous (India’s planning commission puts the total at 37.2% of the country’s 1.2 billion population), but the gap between them and the rich is growing. India can count 55 dollar-billionaires, more than twice as many as Japan.

As India prospers, so the expectations on the nation’s engines of growth increase. The notion of “giving back” to society is not new to Indian businesses. The leaders of India’s grand old industrial houses – Tata, Godrej, Mahindra, Birla and so forth – are paragons of corporate beneficence.

Private philanthropy

Traditional philanthropy still has its place in contemporary India. Some of the nation’s most acute problems – schools that lack educational materials, health clinics short on medical equipment, houses without sanitation – can only be resolved by substantial, targeted funding.

Step forward the private sector. Or so say India’s policymakers. To encourage more corporate giving, the government currently obliges state-owned companies to reinvest anywhere between 0.5% and 5% of net profits in “CSR activities”. Moves are now afoot to extend that obligation to all companies.

Expanding the definition of corporate responsibility from straight philanthropy to a wider ethical and sustainable business practices is a challenge. And it’s a challenge that most Indian companies have yet to resolve.

That’s understandable, says Malini Mehra, founder of the Delhi-based Centre for Social Markets. India has only had an open market for 20 years. Most of its business leaders grew up in an “autarchic economy” characterised by “bounded growth”. Little surprise, then, that “only a handful of companies realise the strategic value of doing good”.

Leading lights

However, though it may only be a handful of companies, their influence is significant. India is already well known for its innovative, street-smart entrepreneurs. Now it’s the country’s social entrepreneurs that are hitting the headlines. This new generation of business innovators are experimenting with commercial models that blend financial returns with developmental outcomes. From low-cost, high volume healthcare to micro, renewable energy, the list is getting longer.

As a consequence, India is fast becoming a test-bed for radical market-based solutions to social and environmental challenges. Hindustan Unilever (HUL), for instance, spent a number of years piloting a low-cost water purifier for the Indian market. Now the product is available in Indonesia, Brazil and a host of other developing countries. “India is a big market in itself and a lot of the problems in the world are represented here,” says Yuri Jain, vice-president for HUL’s water business.

As India’s large corporations begin looking to embrace a wider role in society, corporate responsibility advocates are pushing for an approach that is culturally contextualised. India has the advantage of hindsight, too. Amita Joseph, director of the non-profit Business and Community Foundation, explains: “We believe we can learn from the mistakes – as well as the lessons – of the west”.

In that respect, companies would be advised to “walk the talk”, Joseph says. Their “social licence to operate” depends on it. Regulators, for one, are watching closely.

Business has so far won its fight to keep corporate responsibility voluntary. Yet that could quickly change. At present, the private sector is known more for bypassing regulatory norms and abetting corruption than acting responsibly. Expect more red tape, not less, if corporate practices do not tangibly improve soon.

Evidence of a gradual embrace of strategic corporate responsibility is apparent. India has 154 business signatories to the Global Compact. About a third of the largest 100 companies now issue corporate responsibility reports, according to a recent survey by KPMG.

As India’s economy continues to grow and internationalise, sustainable business will grow with it. Don’t expect an Anglo-Saxon identikit model, however. India does things in its own way.

Corporate responsibility practices among India’s largest 100 firms

- 31 report on corporate responsibility

- 73 integrate corporate responsibility information into their annual reports

- 25 have systems for measuring and managing social and environmental issues

- 16 have a corporate responsibility strategy in place

- 7 disclose the business risk of climate change

- 4 disclose corporate responsibility risks in their supply chains

Source: KPMG Corporate Responsibility Survey 2011, based on top 100 companies by revenue

Oliver Balch is author of India Rising: Tales from a Changing Nation, to be published by Faber & Faber in May 2012.