On the eve of his Stories to Watch 2018 address, Terry Slavin talks to World Resources Institute president Andrew Steer about what it will take to scale up action on climate and the SDGs

How do you help bring about a tipping point on huge issues like climate change, rampant deforestation, or the scandal of one-third of food produced globally being wasted when 800 million people go hungry?

Such are the questions that preoccupy Andrew Steer, CEO and president of the World Resources Institute, the Washington DC-based research centre that spans more than 50 countries, has offices in seven, and more than 700 experts and staff.

Tomorrow WRI will hold its Stories to Watch press conference, where Steer will share his insights on what 2018 will hold for environment and international development to invited journalists, business people and policymakers. The annual event, now in its 15th year, will be live-streamed and gets attention from around the world.

I had a sneak preview when I sat down with him at the UN climate conference in Bonn in November, and asked him which, of the six issues that WRI is most involved in – food, forests, water, climate, energy security and cities – he considers the biggest priority.

No individual organisation can scale anything, especially a humble NGO like ours, proud as we are of the brilliant work of our 700 staff

The soft-spoken Brit, who ioined WRI in 2012 after senior roles at the World Bank and in the UK’s Department for International Development, declines to nominate any stand-out issue. “They are pieces of a jigsaw puzzle,” he said. But the pieces have to be arranged in a way that they have the most impact.

“We just approved a new five-year strategy at our board meeting last month [October], and we decided to focus on what it takes to get encouraging trends to scale,” he said.

“Our motto is ‘count it, change it, scale it’. We are very good at counting, with our research and analysis, and we are quite good at changing, working as we do with cities and corporations. But scaling is very different. No individual organisation can scale anything, especially a humble NGO like ours, proud as we are of the brilliant work our 700 staff do.”

Few working in sustainable business would think of WRI as a “humble NGO”. The institute is a hugely respected voice on the global stage, partnering with UN organisations, other environment and human rights groups, governments and companies with a focus on solutions, including its Global Forest Watch web application (about which more later), which uses satellites and algorithms to allow near real-time monitoring of deforestation. But Steer is focused on WRI increasing its impact.

“The question is what is it that determines a positive tipping point? How do you go from something [where there seems to be no movement] to something that suddenly bursts open,” he asks.

In renewable energy we’ve crossed the tipping point. There are still some countries increasing use of coal but the writing is on the wall

He gives the example of maternal mortality. For 40 years there was no progress on lowering the rate of women dying in childbirth every year. Then between 1990 and 2015 the rate fell by 44%. Another is lead in gasoline – something that it took the US 22 years to phase out. Five years later, another 100 countries had followed.

“In renewable energy we’ve crossed the tipping point,” Steer says. “Yes, there are still Asian countries – not including China – that are increasing their use of coal for electricity, but the writing is on the wall. The tipping point is almost there now.”

He also thinks a tipping point has been reached with corporate commitments to deforestation-free palm oil. This is from zero commitments six years ago. “Then Nestle committed, Unilever committed. Then it was stuck for a while. And suddenly we now have 92% of producers and traders committing to deforestation-free palm oil.” He hastens to add that companies still have a long way to go in implementing those commitments.

What brought that tipping point about? Steer downplays it, but perhaps one of the biggest catalysts has been Global Forest Watch, which WRI launched in February 2014 with the help of Google, “which gave us millions of dollars in pro bono help”, and a host of other governmental, corporate and NGO partners. “Suddenly we are able to show everybody what’s happening to the forest, down to one-tenth of a hectare, anywhere in the world, every week.”

To get to tipping points your need coalitions of like-minded decision-makers who encourage eachother to be more ambitious

This helped generate pressure from consumers and responsible investors in the West. Meanwhile in Indonesia there was a push from President Joko Widodo’s government, “which wanted to do the right thing” by putting a moratorium on new palm oil plantations and focusing on increasing the productivity of smallholder farmers, which had languished compared to commercial palm concessions. Meanwhile governments, including the UK and Norway, weighed in with commitments to source 100% sustainable palm oil.

WRI is part of the Tropical Forest Alliance 2020, the global public-private partnership, funded by the Norwegian and UK governments and hosted by WEF, in which partners take voluntary actions, individually and in combination, to reduce the tropical deforestation associated with the sourcing of commodities such as palm oil, soy, beef, and paper and pulp.

“In order to get across tipping points, you need a combination of things,” says Steer. “One very, very important element is coalitions of like-minded decision-makers who gradually encourage each other to be more ambitious.”

In an attempt to help induce a tipping point on broader climate action, WRI hosts the secretariat of the NDC Partnership, launched at COP22 in Marrakesh, which helps 65 member countries turn their nationally determined contributions to fighting climate change into meaningful action with financial and technical assistance.

Another example is WRI’s involvement in setting up the Champions 12.3 project to mobilize corporate and NGO action towards SDG target 12.3. This aims to halve the amount of food loss and waste by 2030, and launched at the World Economic Forum in 2016.

“We looked at that SDG [12.3] and thought: who is going to make that happen? We came to the conclusion that, wonderful as UN agencies are, it will take [a platform] that is much more multi-stakeholder.”

60% of the world’s largest food companies have committed to cut food loss and waste

The “champions”, all of them either senior UN officials, government ministers or CEOs, now number 40, and the platform is chaired by Dave Lewis, CEO of Tesco, the first UK retailer to publish its food waste data. Liz Goodwin, former head of UK NGO Wrap, which has led the battle against food and packaging waste in Britain, sits on the board as head of food loss and waste at WRI.

The impact in a short time has been impressive. According to its first progress report last year, 60% of the world’s largest food companies by revenue have now set food loss and waste reduction targets in line with SDG 12.3, and half of those are working with their suppliers to bring them into line.

All of the platforms that WRI devotes its resources to, says Steer, combine “serious analysis, great data, and policies that have been proven to work, illustrated and well-communicated. All have a coalition of decision-makers that we then use as champions and engage at the political level, the technical level and, very importantly, the financial level.”

Our time nearly up, I ask Steer a final question. Which of the three main stakeholder groups –governments, civil society, companies – are most critical to driving through solutions. He doesn’t hesitate.

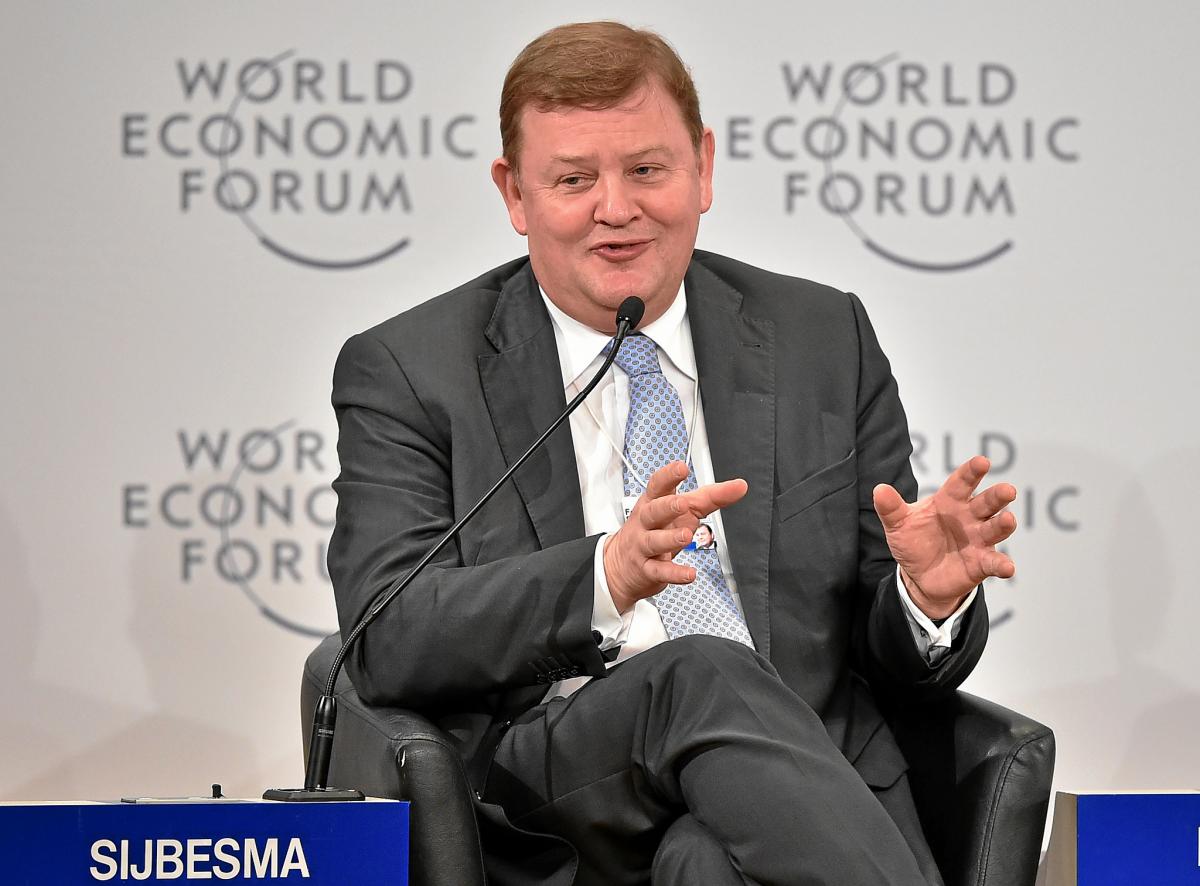

“Without business there would be no solutions to any of these problems. We’ve seen an incredible shift from the days when governments set rules and the private sector grudgingly implemented them,” he says. “This morning I met with Feike Sijbesma [chief executive of DSM], who gave the opening speech at the plenary [of COP23]. He then left me to speak to 30 [climate] negotiators. He runs a chemicals company. Why do they want him? Because he’s a total leader.”

Sijbesma co-chairs, with Canadian environment minister Catherine McKenna, the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition, which is leading a global push for carbon pricing, another platform that WRI is working with.

“Business is absolutely indispensable, but there’s no silver bullet to any of these problems,” says Steer, before returning to the analogy he began our interview with. “It’s a jigsaw puzzle and the pieces not only need to be put on the table, they need to be put down in the right sequencing so it comes together. That’s hard work, and it’s not traditionally what environmentalists have been good at. You don’t get there just by campaigning. You get there by smart coalition-building.”