A unique sustainability culture is developing in China, guided by state control, independent domestic organisations and international partnerships

At some stage in the next decade and a half, China is expected to overtake the US to become the world’s largest economy. This is a return to the long-term norm. For the first 18 of the past 20 centuries, China was the world’s largest economy. Hence, rather than referring to China as one of the “emerging markets,” we should more properly talk of the re-emergence of China. This Chinese renaissance will impact not just international relations and economics, but everything from fashion to sport.

It is inconceivable that this will not also include the theory and the practice of corporate responsibility. To western eyes, there is no shortage of responsible business issues in China today. These include issues such as working practices, health and safety, collective bargaining rights, corruption, food safety, water usage, the treatment of migrant workers, social inequalities, technologies for and management of “smart cities”, the rapid ageing of the Chinese population, and the respect of intellectual property rights.

Greater attention to corporate responsibility (or CSR as it is still more commonly referred to in China), both by Chinese companies and by companies from the rest of the world doing business in China, is being driven by numerous factors.

Capitalism meets tradition

Even casual visitors to China are fascinated by the complex interplay of managed capitalism, Confucian and other philosophical traditions, rapid urbanisation and the sophistication of a burgeoning Chinese middle class, and how all of this is influencing and being influenced by China’s growing inter-connectivity with the rest of the world. Much of the early debate around corporate responsibility in China came from the growing number of foreign multinationals establishing themselves in the country in the 1990s.

These companies introduced international responsible business practices into their Chinese operations; through codes of conduct and supplier codes they started to put requirements for health and safety, environmental standards and worker conditions onto their Chinese suppliers. Discussion ratcheted up after China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2001 helped the country to assume the mantle of the “world’s factory”.

A succession of product safety and other corporate scandals in China over the past decade has increased the interest of the Chinese authorities and the public in corporate responsibility. It is recognised that food contamination, shoddy construction practices (exposed after the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, for example), suicides in the electronics industry, intellectual property theft, and other cases of corporate irresponsibility have stoked domestic protests and damaged China’s reputation internationally.

As more Chinese companies internationalise through both expansion overseas and acquisitions, the image of “China Inc” becomes increasingly important. Domestically, the rapid growth of internet usage and social media in China is driving pressure for greater transparency and accountability – both for companies and for other organisations in China.

Local air quality measurements, for example, are now reported in the media. Some 90% of Chinese millennials think it is their responsibility to share feedback after a good or bad brand experience – compared with 66% of US millennials. Bill Valentino, who has lived and worked in China for more than a quarter-century and is now a visiting professor at Tsinghua and Beijing Normal Universities, notes:

“The fact that China is increasingly online and connected has caused a revolution in communications which has given the Chinese public previously unimaginable abilities to monitor companies and widely and quickly disseminate information on actions that they perceive as irresponsible or unsustainable.”

The 2006 revisions to Chinese company law placed a requirement on companies to “comply with laws and administrative regulations, abide by social morals and business ethics, operate honestly and in a trustworthy manner, and accept supervision by the government and the public, to fulfil their social responsibilities”. The Communist Party of China has emphasised corporate responsibility as a way for enterprises to promote the Harmonious Society – the very Confucian concept which has been at the heart of CPC thinking in recent years. According to Valentino:

“China’s economic miracle is anchored in social stability. Its ongoing economic success seeks sustainable growth based on a new ideology of the Chinese government that focuses on a more balanced society.”

As a result, the agency that controls the ownership of China’s 114 largest state-owned enterprises (SOEs), known as SASAC (The State-Owned Assets Supervision and Administrative Commission of the State Council), issued “guidance for large SOEs on their social responsibility obligations” at the beginning of 2008. The guidelines position corporate responsibility as a key component of the transformation of SOEs into modern corporate institutions and as a means for enhancing competitiveness. Since the 114 largest SOEs produce more than half of China’s goods and services, this has had a significant impact.

Chinese thinkers are, therefore, synthesising Chinese philosophical traditions, international ideas and contemporary practices to develop corporate responsibility with Chinese characteristics – rather as China’s former paramount leader Deng Xiaoping proposed “socialism with Chinese characteristics”. For an accessible summary, see Corporate Social Responsibility in China edited by Yin Gefei and Yu Zhihong (2008).

Growing corporate responsibility architecture

In response to these drivers, and in turn also driving corporate responsibility in China, a number of Chinese organisations have developed initiatives to promote responsible business practice. Among these is the GoldenBee CSR Development Centre. GoldenBee is an initiative of the WTO Tribune magazine, which was originally launched by China’s ministry of commerce in 2003 to help Chinese businesses and policymakers manage the consequences of WTO membership.

The magazine found that it was increasingly covering corporate responsibility-related issues and was identifying the need for practical advice about embedding responsible business practices.As a result, WTO Tribune launched GoldenBee. It mobilises business leadership around thematic programmes of work related to responsible business practices; runs annual awards; has produced a sustainability assessment tool and a corporate responsibility reporting assessment tool; runs workshops, training and customised training (eg on implementation of ISO 26000); provides consultancy services; conducts research; and produces a range of publications in addition to what appears in WTO Tribune and on its CSR China portal. The website was initially financed by the Sino-German CSR Project, which was managed by the German international development agency GiZ.

GoldenBee works closely with about 50 significant Chinese companies and has trained staff from more than 1,000 firms. WTO Tribune/GoldenBee has worked with CSR Europe since 2006, co-organising an annual conference in Beijing each June. As part of this collaboration, it is taking the CSR Europe Enterprise 2020 programme and adapting it to the Chinese context.

The intention is to develop “common vision, common action, cross-border co-operation and shared value” (1) to achieve the sustainable enterprise of the future. GoldenBee has already become a significant Chinese-created and developed corporate responsibility initiative, with strong links to national and provincial governments, and to Chinese trade union and employer federations.

Another indigenous Chinese organisation with a growing interest in responsible business practices is the powerful China Entrepreneur Club, established in 2006 by 31 influential Chinese entrepreneurs, economists and diplomats. (2) The club has produced an annual “Top 100 companies” green ranking since 2010 (3) and publishes the bimonthly Green Herald, founded in 2009. (4)

The growing industry sectoralisation of corporate responsibility coalitions and initiatives seen in other parts of the world is already happening in China. Rolf Dietmar, project director, Sino-German Corporate Social Responsibility Project, says:

“The China National Textile and Apparel Council was the first industry association in China to publish its own guideline, CSC9000T, and to promote this internally within the association. In a further notable development, in December 2010 the China International Contractors Association adopted a guideline for implementing CSR in its member companies, of which there are over 1,300. These companies primarily handle overseas contracts, eg infrastructure projects such as bridges and roads in Africa. The guideline is currently being trialled in 29 pilot companies.” (5)

Among other trade associations developing corporate responsibility initiatives are the Chinese Electronics Standardisation Association (CESA), which has formed a corporate responsibility committee and produced corporate responsibility guidelines based on the ISO 26000 and SA8000 international standards; (6) the China Tea Marketing Association; and the Food Industry Association. Common to all these sectoral initiatives is offering member firms assistance in accessing international markets by understanding and responding to those markets’ sustainability requirements.

Some of the international chambers of commerce in China have “CSR” initiatives including the American Chamber in Shanghai and the EU-China Chambers in Beijing and particularly in Shanghai. The US Chamber of Commerce has co-operated with the All China Federation of Industry and Commerce to hold a US-China Forum on Corporate Social Responsibility Co-operation.

Several of the international corporate responsibility coalitions have initiated projects in China and even established offices in the country. In 2003, the joint efforts of China Enterprise Confederation (CEC) and the World Business Council for Sustainable Development led to the establishment of the China Business Council for Sustainable Development (CBCSD). The CBCSD is a coalition of leading Chinese and foreign enterprises. The CBCSD seems to have been one of the more successful coalitions in engaging a significant number of Chinese firms including the Huafon Group, Jiangsu Shuangliang Group and Sinopec. (7)

Business for Social Responsibility has had an office in mainland China since 2005 (in Guangzhou) and in Beijing since 2007. Since 2004, BSR has operated the China Training Institute (CTI) “to help companies and their Chinese suppliers improve corporate responsibility performance and overall competitiveness through a wide range of training [and] roundtables”. (8) BSR China also undertakes consulting projects focusing on supply-chain management. CSR Europe differs from BSR in terms of its engagement with China. Rather than establishing its own office, CSR Europe has chosen to support the activities of a Chinese partner: the aforementioned WTO Tribune and its associated GoldenBee initiative.

The UN Global Compact (UNGC) has been represented in China since the end of 2001. In 2009, the UNGC formally recognised the creation of the Global Compact Network China Centre and contracted to house the centre’s secretariat with the Beijing Rongzhi Institute of Corporate Social Responsibility. The secretariat is responsible for organising and implementing the UNGC’s various activities throughout China. (9)

The Chinese chapter of the UNGC comes under the auspices of the ministry of foreign affairs. A significant advance in official recognition of the UNGC in China came with the appointment to the UNGC board of Fu Chengyu, chairman of the Sinopec, the state-owned oil and gas refiner. As yet, however, the number of Chinese business signatories of the UNGC remains a tiny percentage of the total of Chinese enterprises.

There are a number of academic centres including the Corporate Social Responsibility Research Centre at Peking University Law School and the China Institute for Social Responsibility at Beijing Normal University’s School of Social Development and Public Policy. There are also several China-headquartered consultancies specialising in corporate responsibility such as SynTao and InnoCSR.

More corporate responsibility reporters

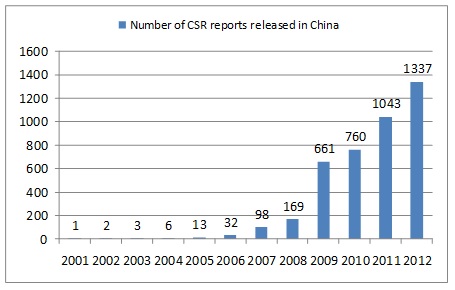

As a result of the SASAC guidelines and other initiatives, there has been a rapid increase in the number of companies in China publishing corporate responsibility or sustainability reports (see figure 1). Since 2009, WTO Tribune’s GoldenBee Initiative and the International Research Centre for Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development of Peking University have been publishing an annual survey of the quantity and quality of corporate responsibility reports produced in China. Their most recent review, covering the first 10 months of 2012, finds that 1,337 corporate responsibility reports were released. This is an increase of almost two-thirds over the previous year, including 103 of the 114 SASAC-controlled SOEs. GoldenBee’s assessment of the quality of the reports suggests some overall improvement but that “negative information and impacts were neglected in the reports”. (10)

Figure 1: CSR reports released in China

Source: GoldenBee and the International Research Centre for Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development of Peking University

Catching-up

While much focus of the Chinese companies has so far been on corporate philanthropy and corporate community involvement, environmental health and safety, environmental protection and education, this is evolving fast. The world’s largest mobile phone company, with its 760 million subscribers – China Mobile – has appeared in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index for five consecutive years (still the only mainland Chinese company to appear in the DJSI). Whereas most Chinese reporters (nearly 95%) still publish “CSR” reports, China Mobile publishes a “sustainability” report. It has adopted a “shared value” approach illustrated by ambitious mobile health programmes.

Rising affluence and growing concern for sustainable development is spurring innovation. In an October 2012 New York Times article, widely quoted in the Chinese media, the influential columnist Thomas Friedman wrote:

“Does Xi Jinping [China’s new leader] have a ‘Chinese Dream’ that is different from the American dream? Because if Xi’s dream for China’s emerging middle class – 300 million people expected to grow to 800 million by 2025 – is just like the American Dream (a big car, a big house and Big Macs for all) then we need another planet.” (11)

Whether, as the Economist argues (12), this Friedman article helped trigger Xi Jinping’s subsequent promotion of the idea of a Chinese Dream, Friedman himself was inspired to write his article by the work of social entrepreneur Peggy Liu, the founder of JUCCCE – the Joint US-China Commission on Clean Energy. Liu is working with social media commentators, marketing agencies and branding experts to make sustainable consumption an aspirational lifestyle in China, and challenging Chinese brands to support this.

Co-creating the future

China is building a corporate responsibility architecture with Chinese characteristics. Specifically, this is likely to be more state-inspired, more shaped by government departments, more linked to national purpose, namely the pursuit of the Harmonious Society, more top-down driven and more focused on collective rather than individual stakeholders.

Each society has to evolve a rich mix of laws, social conventions, collective self-regulation, ethical norms, government policies, individual responsibilities and market dynamics. Around the world, over recent decades, and especially since the early 1990s, there has been a growing interest in the roles and responsibilities of business in society. Corporate responsibility and sustainability have become part of the discourse around globalisation. As China’s re-emergence as a global player accelerates, Chinese theory of, and practice in, corporate responsibility, and the architecture to support businesses in embedding corporate responsibility and sustainability will rightly become important.

They will affect – as well as be affected by – the corporate responsibility architecture elsewhere; both as Chinese companies internationalise and develop their modus operandi for other parts of the world and as Chinese experience and practice influence the work of corporate responsibility coalitions and multi-stakeholder initiatives, first in their work in China, but subsequently, potentially, their thinking and practice too in other parts of the world. This will be an interactive and iterative process in the journey to more responsible business practice globally and towards corporate sustainability. Intense and subtle intermediation and dialogue will be needed to achieve this.

David Grayson is director of the Doughty Centre for Corporate Responsibility, Cranfield School of Management, and a member of Ethical Corporation’s editorial advisory board

____________________________________________

[1] http://csr-china.net/en/ind/goldenbeeforum2020/,

[2] www.daonong.com/English/index.htm,

[3] http://www.daonong.com/English/2011_Press3.html,

[4] www.daonong.com/english/green.html,

[5] R. Dietmar, ‘CSR in China: Recent Developments and Trends’, in oekom CR Review (Munich: oekom research, 2012): 52.

[6]www.sa-intl.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=Page.ViewPage&PageID=1208,

[7] China Business Council for Sustainable Development, http://english.cbcsd.org.cn/cbcsd/chm/index.shtml, accessed 23 July 2012.

[8] http://ctichina.org/v2/en.

[9] UN Global Compact, Local Partners Network Report 2010 (New York: UNGC, 2010, http://www.unglobalcompact.org/docs/networks_around_world_doc/Annual_Report_2010/GCLN_2010.pdf, accessed 23 June 2012). From 2012, the China Entrepreneur Confederation (CEC) replaces Rongzhi to house the secretariat of UNGC China network.

[11] http://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/03/opinion/friedman-china-needs-its-own-d...

[12] http://www.economist.com/blogs/analects/2013/05/chinese-dream-0

China globalisation China Government China Strategy CSR in China David Grayson