With hundreds of companies having failed to act on commitments to be deforestation-free by 2020, Mars Inc is leading Consumer Goods Forum’s work on developing credible new paths to clean up their supply chains

Consumer goods giants are working on radically new approaches to end deforestation in supply chains amid a recognition that hundreds of companies that made commitments to source deforestation-free commodities by 2020 will abjectly fail to meet the deadline.

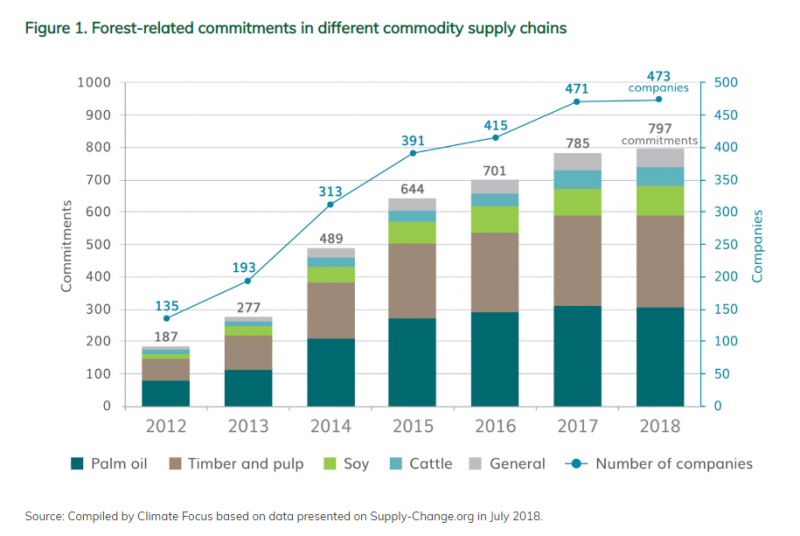

According to The Supply Change Initiative (SCI), which tracks 800 companies with exposure to soy, beef, palm oil and timber – commodities that are together responsible for 80% of all tropical deforestation – 469 have commitments to address deforestation.

These include the 400 members of the Consumer Goods Forum (CGF), which in 2010 pledged to help achieve zero net deforestation in their supply chains by 2020.

Zero deforestation commitments were made without serious consideration to what it would mean and what it would cost

Eight years later, even the Consumer Goods Forum admits the commitment exists largely on paper and few companies will meet the 2020 deadline. A report from the SCI this year found only 6% of companies with commitments have gone beyond making blanket statements in their CSR reports and are actually taking steps to address their high-risk facilities, suppliers, and/or regions of operation.

With companies failing to monitor their supply chains for deforestation risk, this role is being performed by investigative NGOs like Greenpeace and specialist investor analysis company Chain Reaction Research, as previously reported in Ethical Corporation.

They say failure to make good on commitments over a lost decade has had a devastating impact, particularly on deforestation caused by palm oil, which accounts for 59% of commitments, mainly though the sourcing of palm oil certified by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO).

According to a report in September from Greenpeace, palm oil companies that supply the world’s largest brands, including Unilever, Nestlé, Colgate-Palmolive and Mondelēz, have destroyed an area of rainforest almost twice the size of Singapore in less than three years.

In its Final Countdown report, Greenpeace points the finger at Wilmar International, the world’s largest palm oil trader, which despite signing a no-deforestation, no peat, no exploitation commitment in 2013, still gets its palm oil from 18 of the 25 palm oil producers that Greenpeace identifies as having cleared 130,000ha of rainforest since the end of 2015. Wilmar responded by saying it would step up its efforts to meet the end-2020 deadline, using satellite technology and independent verifiers to monitor land use change in its own concessions and those of its suppliers, launch a platform to assess areas of vulnerable forests, and review how it tackles labour and community issues.

Nigel Sizer, chief programme officer for Rainforest Alliance, says although action by governments is key to halting deforestation in the long term “massive reform of public policy in a few short years is unrealistic. The burden does fall on companies. Zero deforestation commitments were made by many companies without serious consideration to what it would mean and what it would cost, and now general counsels, I’m sure, are concerned, even more as 2020 approaches and they have made little progress.”

There is a lot of confusion around commitments. It varies wildly across the hundreds of companies that are making them

“We need to look hard at how much companies are investing in this, what’s preventing them from investing in this, and what is happening at a leadership and board level on these issues and commitments.” One barrier, he said, has been a lack of guidance for companies on what constitutes a deforestation-free value chain, and no standard way to assess and report on progress on achieving one. Partly this is due to a lack of consensus between environmental and social NGOs.

At the end of 2016, a group of 10 NGOs, including the Forest Peoples Programme, Greenpeace, Proforest, Rainforest Alliance, The Nature Conservancy, World Resources Institute, and the World Wildlife Fund started working on an Accountability Framework to provide unified guidance on how to implement credible supply chain commitments. The framework, including an operational manual with commodity and geography-specific guidance, will be finalised next year.

“There is a lot of confusion around the commitments,” says Sizer. “It varies wildly across the hundreds of companies that are making them. The Accountability Framework is a response to this challenge and the request for NGOs to provide a framework and guidance …. Bottom line is the commitments are almost meaningless unless there’s a robust system of accountability to support them.”

One solution being widely promoted is for companies to stop sourcing forest-risk commodities on world markets and source directly from the growing number of jurisdictions around the world that are taking a landscape-level approach to addressing deforestation, integrating land planning, sustainable forest management and commodity production.

According to a report released in September by the Earth Innovation Institute, the State of Jurisdictional Sustainability, 28% of the world’s tropical forests are located in 39 subnational jurisdictions that have taken this holistic approach – and half of them have seen deforestation drop below projected levels, adding up to 6.8 gigatonnes of avoided CO2.

You need to strike the right balance between produce and protect. It’s easier for governments to favour the produce side rather than protect

Marco Albani, former director of Tropical Forest Alliance 2020, a partnership between the CGF and the US government to fight commodity-driven tropical deforestation, told the Oslo Tropical Forest Forum session that the fact that large areas of tropical forest remain uncovered by corporate commitments of any kind mean it is important for companies to support approaches that cover entire landscapes.

This gap is most obvious in palm oil. According to a recent TFA 2020 report, Indonesia and Malaysia produce 85% of the world’s palm oil, yet fewer than one-third of the combined production area is RSPO-certified, mainly because of the prevalence of smallholder farmers.

An agreement by Unilever with district governments in Indonesia’s Central Kalimantan in 2015 to preferentially source zero-deforestation palm oil from local smallholder farmers, and a similar commitment by Marks & Spencer, are pioneering attempts to plug this gap in palm oil.

But Ignacio Gavilan, director of environment at the Consumer Goods Forum, said that while some CGF members are looking at the feasibility of jurisdictional sourcing, “they need proof that it works. You need a very compelling argument to switch suppliers for reasons including competition.”

He said members have raised concerns about governance. Such agreements “need to strike the right balance between produce and protect,” he said. “And it’s easier for governments to favour the produce side rather than protect.”

Professor William Boyd of the University of Colorado is project leader for the Governors’ Climate and Forest Task Force. Started 10 years ago by California and four Brazilian states to work together to tackle deforestation, the GCF today includes 39 subnational governments in 12 countries.

If you just certify farm by farm,you could have islands of sustainable supply chains in a sea of deforestation

Boyd says adopting a jurisdictional approach to sourcing could help companies make a real contribution to reducing deforestation, as evidenced by success in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso with sustainable soy. (See, Sowing more sustainable soy production in Brazil’s Cerrado region)

“If you just do it farm by farm, mill by mill to certify your commodities are deforestation-free you could have islands of sustainable supply chains in a sea of deforestation. … We really think this broader jurisdictional approach is critical to the success of that effort and the two things are complementary and need to come together.”

Barry Parkin, head of sustainability and procurement at Mars Inc, is also chairman of the World Cocoa Foundation, which helped to bring about last year’s ground-breaking Cocoa & Forests Initiative, framework agreements between cocoa companies and manufacturers and the governments of Ghana and Côte D’Ivoire. (See, Fightback against deforestation in Africa focuses on small farmers)

He said it offered a path to deforestation-free cocoa in West Africa, not just for signatory companies, but for any company sourcing cocoa from Ghana or Côte D’Ivoire. “The good thing about the Cocoa & Forests Initiative is it is really clear what industry has to do and what governments have to do, and they are working together. It’s the best model we have across any raw material for stopping deforestation.”

But it is not an approach that will succeed on a large scale for palm oil, he says, because there is not the same level of government motivation. There are also too many buyers, with about 80% of volumes going to Asian markets.

“Jurisdictional approaches are just about finding places where you have all the actors who want to work together and crowding in investment. …. That may be part of the theory of change, but it’s not the whole answer and it won’t get us there fast enough,” said Parkin. “Companies still have a big responsibility to simplify and to clean up their own supply chains.”

We have to move further and faster to clean up our supply chain, and that will require radical simplification

Parkin and his team have spent the last two years trying to do just that, mapping the company’s supply chain for 10 critical raw materials as part of the company’s $1bn Sustainable in a Generation Plan.

The company has adopted a radical new sourcing strategy, to stop treating its raw materials as commodities, bought purely on price, and source directly from farmers.

While it has managed to do this with ingredients like vanilla, palm oil is proving more difficult to transform, Parkin said, though he maintains that Mars will be deforestation-free in palm oil by the end of 2020.

“The company had been hoping the whole [palm oil] industry was going to change, but it’s clear that it is not going to change a vast amount. … We have to move further and faster to clean up our supply chain, and that will require radical simplification, longer-term contracts directly with farmers, and stronger due diligence on the ground.”

At the same time, Mars has not given up on collective action. It has been playing a leading role on a Consumer Goods Forum working group that has been consulting widely to come up with a “set of new theories of change” on deforestation, in recognition of the failure of the 2020 commitments.

He said the strategy, which is expected to be published next year, will go “way beyond current practices” of relying on sustainability certification schemes of relying heavily on sustainability certification schemes such as RSPO.

It’s an investment. But in the end you get a sustainable supply that is completely free from deforestation

“RSPO has its challenges in terms of its levels of ambition and its governance. "It’s been helpful .... but the rate of deforestation is broadly where it was 10 years ago, despite many, many players in the industry being 100% certified.”

Jamison Ervin, who leads at the UN Development Programme on the New York Declaration on Forests, says she believes Mars’s approach offers the best chance for companies to stop deforestation in their supply chains.

By having an agreement with communities about when they will buy, and guaranteeing a purchase price, she said, communities can put long-term plans in place and shift away from cutting down forests.

“It’s going to cost something, it’s an investment. But in the end you get a sustainable supply that is completely free from deforestation.”

Terry Slavin is editor of Ethical Corporation.

This article is part of the in-depth Deforestation briefing. See also:

Sowing more sustainable soy production in Brazil’s Cerrado region

Fightback against deforestation in Africa focuses on small farmers

Growing concerns: the companies innovating to cool the planet

Why satellite surveillance isn’t enough to turn the tide on deforestation