Diana Rojas charts a year in which Interface hired lobbyists for the first time, Patagonia filed a lawsuit against the federal government and the We Are Still In coalition grew to 2,500 members

Holiday shoppers on outdoor goods retailer Patagonia’s website earlier this month could not miss the stark black and white message on its homepage: “The President stole your land…. This is the largest elimination of protected land in American history.”

The webpage protest, in response to the Trump Administration’s announcement it would shrink two national natural monuments – Utah’s Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument – culminated a year of activism on the issue by the company. Patagonia then announced it would sue the federal government.

“Protecting public lands is a core tenet of our mission and vitally important to our industry, and we feel we need to do everything in our power to protect this special place,” wrote Patagonia CEO Rose Marcario in Time Magazine.

The Trump Administration has sent a siren call to American corporations tempting them into a race to the bottom. Thankfully, some have recognised that their long-term viability demands a race-to-the-top approach to globalism

The response from the Republican Party took aim at Patagonia – and its customers. The House Committee on Natural Resources tweeted a mock-up of the Patagonia homepage: “Patagonia Is Lying to You – A corporate giant [is] hijacking our public lands debate to sell more products to wealthy elitist urban dwellers from New York to San Francisco”

US President Donald Trump spent his first year in office trampling on progressive ideas – from a travel ban targeting Muslims to rescinding the country’s global climate mitigation pledge to drilling in hitherto protected wilderness. And by and large the corporate response has been defiance and a public commitment to stay the course.

“The Trump Administration has sent a siren call to American corporations and aims to tempt them into a race to the bottom. It has promoted lower ethical and emissions standards, less transparency, and a short-term transactional perspective on competing in the global marketplace,” said Paul O’Brien, Oxfam America vice-president for policy and campaigns. “Thankfully, some ethical corporations have recognised that their long-term viability demands a more strategic race to the top approach to globalism.”

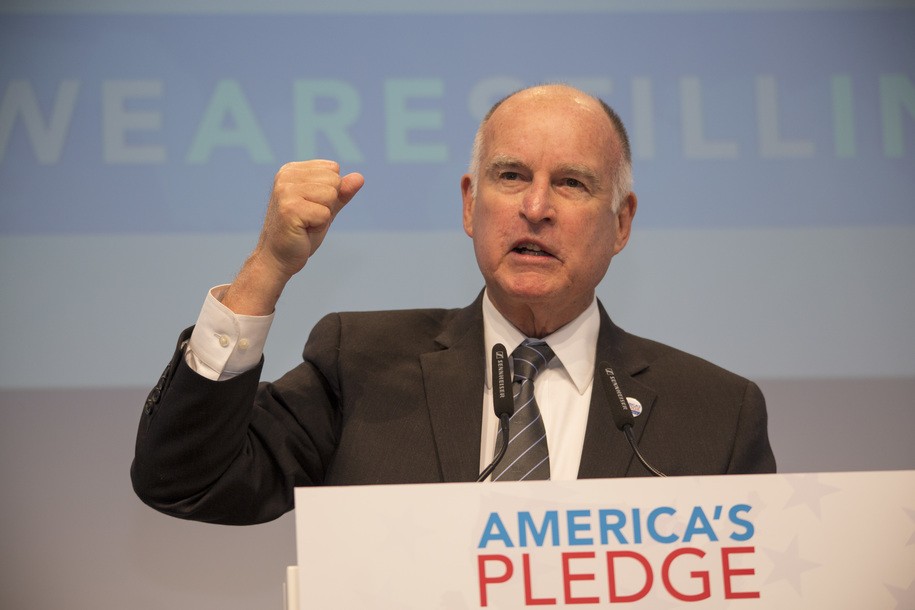

At the COP23 in November in Bonn, the newly formed America’s Pledge on Climate, led by California Governor Jerry Brown and UN Special Envoy for Cities & Climate Change Michael R Bloomberg, issued a report quantifying non-federal action since the official withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in June. Among other findings, it notes that the number of states, cities and businesses that have pledged to live up to the US commitment in the Paris Agreement represent more than half of all Americans and $6.2trn of the US economy, and would make up the third largest economy in the world. (The We Are Still In group now has some 2,500 members).

The global We Mean Business Coalition counts 646 companies as members of its various initiatives, like Science-Based Targets (committing to lowering GHGs) and RE100 (committing to use 100% renewable energy). Nearly a quarter (150) are American.

We need to change the bigger system, which requires a more uncomfortable position for the CEO. It’s not easy to pick up the phone and call Rex Tillerson

“The people who are in the We Are Still In coalition didn’t do it from a do-gooder position. They did it because they had made very public commitments around climate reduction policies,” said Erin Meezan, chief sustainability officer at Interface, the Georgia, Atlanta-based modular carpet company that has for two decades been on the vanguard of corporate climate mitigation and the circular economy. “Many more businesses are asking themselves: what’s our role here?...This climate calls for more advocacy. And I’m encouraged to see some of the bigger things, like [the reaction to] Bears Ears.”

An increase in corporate public advocacy was a big change in 2017, she said. On the eve of Trump’s announced withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in June, Meezan and CEO Jay Gould put in calls to the White House and Secretary of State Rex Tillerson to dissuade them – a first for both. (Their calls weren’t returned). The company also hired a lobbyist for the first time in 2017 to advocate for California legislation mandating carpet recycling (it passed), and Interface is now considering expanding lobbying efforts to more states, she said.

“We need to change the bigger system, which requires a more uncomfortable position for the CEO. It’s not easy to pick up the phone and call Rex Tillerson,” said Meezan.

In an interview at COP23, Eric Olson, senior vice president of BSR, noted that while the proportion of American businesses signing up for public initiatives may be “technically” modest, they represent a big share of US employment. Large corporations (with more than 1,500 employees) employ 38% of the private sector workforce in the US.

“Eighty per cent of our businesses are small businesses, and it’s a lot harder for them to play that same kind of game,” said Olson. “Our government backing away inspired other people to step up even more, which is what we hoped.”

Meezan said businesses now need to evaluate their strengths and capacity to enact change: the CEO of a big corporation like GE might be able to hop on a plane and demand a meeting at the White House, but the 5,000-employee Interface can do more by influencing other businesses. Poised to meet its zero carbon goals by 2020, Interface this year launched its Climate Take Back mission, which includes using carbon as a resource. In June it unveiled its prototype Proof Positive carbon negative tile. Interface has open-sourced its Climate Take Back materials, said Meezan. So far it has been downloaded 1,600 times, she said.

The White House began its assault on progressive environmental and climate policies with the deletion of all references to climate change from its website on day one of the Trump Administration. By March, the White House shut down the Clean Power Plan, which aimed to cut GHG emissions, approved pipelines, cancelled methane emissions reporting, as well as guidelines for GHG emissions in environmental reviews. By April, it deleted funding for the Green Climate Fund, a multilateral mechanism to assist developing countries in climate change adaptation and mitigation practices. And in June, it announced its retreat from the Paris Climate Agreement.

In the latter half of 2017, the White House made an historic proposal to auction off 77 million acres in the Gulf of Mexico for oil and gas leases in October. And by late November it approved oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and awarded an oil exploration request in Arctic waters.

Nevertheless, Kevin Rabinovitch, global sustainability director for Mars, Inc, said the country’s corporate response in favour of sustainability should continue to grow as it is being driven by profits more than politics. In September, Mars announced its $1bn Sustainable in a Generation Plan, which includes a 67% reduction in GHG emissions in its supply chain by 2050. It had already pledged 100% renewable energy when it joined RE100 at that initiative’s inception in 2014.

Regulations are a major driver for corporate action, but so is shareholder pressure, brand reputation,and rapidly declining prices for renewable generation

“It’s driven by science and by what we can do to capture opportunity and manage risk,” he said. “There are many things pushing down GHG emissions other than the statements and positions of the US White House…. And happily, what’s right for our business is right for people on the planet.”

Kyle Danish, a partner at Van Ness Feldman, an energy and environmental legal practice in Washington, DC, said he has “no illusions about the altruism of corporations”, but he does not believe that corporate America will do an about face on sustainable business because of the Trump Administration deregulation. Corporate America, especially in the energy sector, has “taken the long view” that regulation and carbon constraints of some kind will be inevitable, said Danish, also an associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

“To be sure, regulations are a major driver for corporate action, but there are other very significant drivers that are not motivated by altruism: shareholder pressure, brand reputation, rapidly declining prices for renewable generation, etc,” said Danish.

Indeed, the lower cost of renewables has set the stage for some of these successes, according to the America’s Pledge report. For example, the cost of solar power and vehicle batteries has dropped 80% since 2010 and this August the Department of Energy announce that its SunShot target to make solar affordable was met three years early.

According to an October report by CDP one of the biggest game-changers in the US renewable energy market is the increase in energy contracts signed with businesses and other big users – from 5% in 2013 to 40% of wind contracts last year. And America’s Pledge points out that 62 US-based Fortune 500 companies have set renewable energy targets, with five – Autodesk, Starbucks, TD Bank Group, Voya International and Google – having reached their 100% renewable goal in 2017.

This economic reality dulled the bluster of the Trump Administration’s vow to bring back coal. After the Department of the Interior lifted the three-year moratorium on federal coal leasing earlier this year, it received only one new lease application. And of the 44 federal leases, eight were suspended by their new owners and five were cancelled.

Similarly, despite the Trump Administration’s re-opening of a review of fuel efficiency standards in cars and trucks, US-based General Motors, the world’s third largest auto producer, announced in the autumn an all-electric future, beginning with two new electric models in 2018 and 18 more by 2023. Ford also announced that it would be studying fully electric cars, and plans to deliver 13 electrified vehicles in the next five years.

However, America’s Pledge warns that without federal efforts, the current sub-national commitments will fall short of meeting the US pledge under the Paris Agreement to reduce emissions between 26-28% below 2005 levels. “I think the real problem is this,” says Danish. “Just maintaining the current trajectory, while better than reversing course, is not nearly enough.”

Diana Rojas is a freelance writer based in Washington, DC and a regular contributor to the Ethical Corporation, focusing on environmental policy and sustainability issues. Diana is fluent in Spanish and Portuguese.

Patagonia Interface We Are Still In BSR We Mean Business RE100 America's Pledge Science Based Targets Jerry Brown