People flood to city factories, then export growth hits the wall. It’s all change in China

The history of sustainable business and corporate responsibility in China has been problematic. China’s 30-year rise to become the workshop of the world involved corner-cutting and the de-prioritising of issues such as the environment and business ethics. Bribery and corruption remain major problems, while China’s one-party state means no independent workers’ organisations are allowed. The only union remains the official state union, widely dismissed by workers as ineffective.

And while things have slowed, the past 30 years have seen an unprecedented internal migration from the over-populated countryside to the urban manufacturing regions – the proportion of Chinese people living in urban areas reached 50% in 2011.

China’s manufacturing backbone has been low-end assembly. This meant that the early progress of corporate responsibility in China, according to Wang Liwei, an activist who runs the Charitarian magazine, was centred heavily on factory audits, trying to ensure good conditions, training in health and safety and addressing migrant worker concerns.

Wang points out that sometimes these initiatives were supported by Beijing, but often they were viewed with suspicion. The Charitarian has reported on the government’s persistent objections to worker councils established in some foreign-owned China-based companies. Foreign firms and brands particularly have been monitored closely and there have been repeated campaigns involving many household brands around issues such as factory conditions and pay – Prada, Wal-Mart and others have been caught in this trap.

The Beijing government has been keen to show the public that foreign brands break the rules. Bill Dodson, author of the recent book China Inside Out, notes that in the past two years Beijing has watched closely for foreign rule-breakers, bashing them through a PR campaign declaring to the Chinese people that “it’s not one rule for the domestic firms and another for foreigners”.

From focused to broad-based

It’s fair to say that after an initial flurry of factory-based corporate responsibility projects in the 1990s there has been a reorientation towards more charitable or broad-based initiatives targeting government relations and consumers.

There are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, many factory-based initiatives proved unworkable because of the highly transient nature of the factory workforce migrating between factories as well as back and forth to the countryside.

Secondly, many organisations found that trying to monitor programmes across multiple factories was impossible. A medium-sized clothes retailer may contract with 200 factories, for example, a number that can quadruple when subcontractors are included.

Thirdly, Beijing and local officials were hostile to some programmes, making them effectively unworkable.

Finally, many corporations decided that their efforts were better used in building goodwill with Beijing and consumers.

Only a few short years ago, China was in a very different position economically. The worst of the global recession was still to come and China’s manufacturing sector was riding high on export orders. The initial impact of the recession for China was to see a fast slowdown in manufacturing orders, across almost every sector, primarily from North America and the EU.

There was a rash of factory closures in 2010 and 2011. At one point these became so bad – especially around Guangdong – that the authorities stepped in to ensure factory owners did not attempt midnight flits, leaving the factory and the country (many of these factories were owned and managed by Hong Kong or Taiwanese entrepreneurs).

In some highly publicised instances, workers occupied the factories fearing lost wages. Many factories have only been able to continue through reductions in working hours.

In the worst affected regions, especially Guangdong and around Zhejiang and Jiangsu, local governments have stepped in with stimulus packages including tax breaks and other incentives. Simultaneously the rapid expansion of China’s domestic consumer market has helped some export-oriented firms realign domestically. While this has not completely managed to “rebalance” the economy as Beijing would like – away from overdependence on exports – it has helped.

Costs increase

Still, costs have risen everywhere, from inputs and raw materials to land prices, rents, energy, administration, shipping and, of course, labour.

Wages have become a key issue as China moves away from its demographic “sweetspot”. Quite simply the number of 16-24-year-old workers with non-arthritic fingers is running out; costs for migrant and low-skilled workers are rising; urbanisation is slowing.

This is the new reality of China’s manufacturing sector: no longer the world’s cheapest location, it must compete with countries just moving into their own demographic sweetspots – India and Bangladesh, for example.

Peter Goff, a corporate responsibility activist and charity organiser in Sichuan province, sums the situation up: “The material social conditions have changed – from too many workers to too few, from low wage to increasingly higher wages. It’s a new social economy and will need a new approach to corporate responsibility.”

Paul French, China editor, has been based in China for over 20 years. He is a partner in research publisher Access Asia-Mintel.

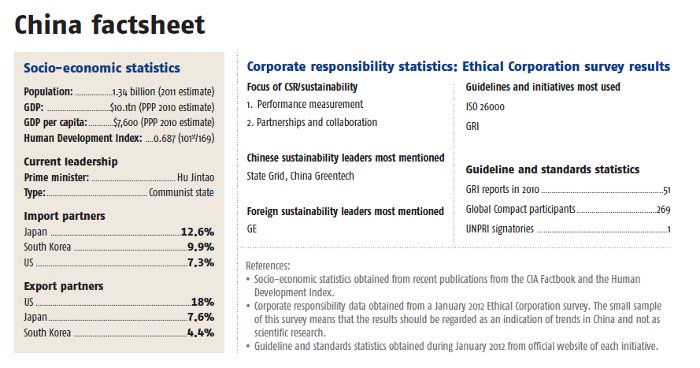

China corporate responsibility factsheet