Slavery, still pervasive across the globe, has proven difficult to tackle for multinationals whose leaders are far removed from the people producing their raw ingredients. But with help, companies are working their way down the supply chain to eradicate the problem

Modern-day slavery has many faces, all of them imprinted with desperation. It is children working in cocoa fields in Ivory Coast, without protection from the machetes they are wielding or the pesticides they are applying. It is teachers, lawyers and children in Uzbekistan, forced to spend two months harvesting cotton every year. It is fishermen in Thailand who were abducted and sent off to sea, where they work with almost no rest and are sometimes kept in cages during the few hours a day they are not hauling up nets or packing fish.

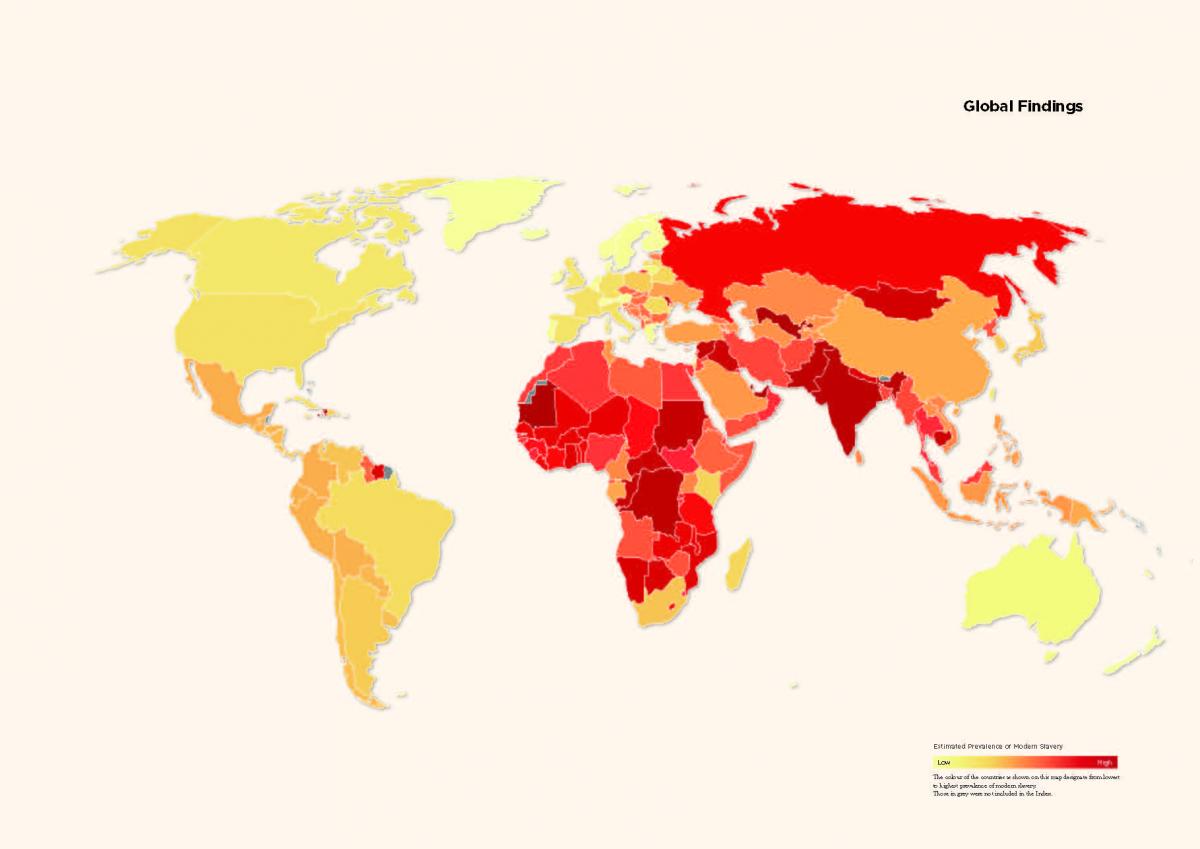

Around 36 million men, women and children worldwide currently are trapped in slavery, 20% more than previously thought, according to the 2014 Global Slavery Index (GSI). The higher estimates are attributed to changes in data collection methods and classifications. Twenty-first century slavery includes human trafficking, forced labour, debt bondage, forced or servile marriage, and commercial sexual exploitation, the GSI says.

Numbers have been rising over the past decade. In 2005, the estimate for those in modern slavery was about 12 million and in 2012, it was up to 21 million, although in the past, slavery and trafficking were measured differently, notes Jakub Sobik, the press and digital media officer for Anti-Slavery International in the UK.

And it is ubiquitous. “It happens in Mauritania, where people are the full property of their masters,” says Gina Dafalia, head of communications for the Walk Free Foundation, an Australian-based organisation committed to eradicating slavery. “[It happens] in Indian brick kilns where generations of families are enslaved, in farms in the UK and Australia and in fishing boats off the coast of Thailand. Every single country is affected.”

Five countries host 61% of the world’s slaves – almost 22 million people. India has the largest number of enslaved people, estimated at 14.3 million, followed by China with 3.2 million, Pakistan with 2.1 million, Uzbekistan with 1.2 million and Russia with 1.1 million.

Countries with the highest proportion of their population in modern slavery are Mauritania and Uzbekistan with 4%, then Haiti at 2.3%, Qatar, 1.4%, and India, 1.14%, according to GSI.

The majority of slave labourers are working in private sector industries, such as manufacturing, construction and agriculture. Modern slavery permeates the supply chains of many businesses around the world. “If a company is sourcing clothing from Bangladesh, electronics from Malaysia or China, bricks from India, cotton from Uzbekistan, minerals from West Africa, seafood from Thailand, or even tomatoes from Spain or Florida, chances are their products are manufactured using modern slavery,” says Dafalia.

As hard as it is to believe that an anachronistic practice such as slavery exists in the era of electric cars and 3D printers, forced labour continues because is profitable, hard to identify and sustains many industries. The International Labour Organisation estimates the profit from slavery is $150bn a year.

In the field

“Slave labour occurs in places difficult to detect; both because the labour is often in secluded places such as fields, mines, fishing boats or backrooms in factories, and because the slaves feel they have no ability to reach out for help,” says Paul Hirose, CSR advisor to the Tronie Foundation, which focuses on eliminating slavery and helping victims rebuild their lives.

Slavery continues despite 12 international conventions and more than 300 treaties banning it, says Dafalia. “Slavery is not a stand-alone practice that we can just ban and expect it to stop,” she says. “It is part of our global economy and society and it is linked to global supply chains. In many countries it is institutionalised. Other factors are also driving the resurgence of this crime such as the increasing transnational movement of workers, many of them highly vulnerable to exploitation.”

For many people, slavery begins through debt. People desperate for work leave their home countries, lured by unscrupulous recruiters, who charge huge fees for the right to work in other countries – and the migrants pay those fees by borrowing. But their salaries are never enough to pay off the debt. “The migrants are at a disadvantage straight away,” says Anti-Slavery International’s Sobik. “They may not be legal, they don’t know the language, they can be blackmailed, they lack access to what the state provides, there is a lack of rule of law and they tend to get exploited.”

Sobik adds: “In India, there is a form of bonded labour; someone borrows money and the way to repay it is to work. The control of the debt is on the side of the powerful and the rich. It takes years and generations to repay the loan. They cannot leave the employer; they don’t have the control.”

The 2014 GSI report notes that in India, slavery takes the forms of “inter-generational bonded labour, trafficking for sexual exploitation and forced marriage”. The report says evidence suggests that members of lower castes and tribes, religious minorities and migrant workers are disproportionately affected by modern slavery. “Modern slavery occurs in brick kilns, carpet weaving, embroidery and other textile manufacturing, forced prostitution, agriculture, domestic servitude, mining, and organised begging rings.” The report cites accounts of women and children from India being recruited with promises of non-existent jobs and later sold for sexual exploitation, or forced into sham marriages.

Slavery in Thailand’s fishing industry recently garnered widespread attention, largely because of an Associated Press investigative story published in April. The article cited the plight of men from countries including Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos, who thought they were signing up for construction or other jobs, only to be taken to fishing vessels, where some of them remained captive for years, often spending months at sea. Men reported working long hours with no pay and little food. Some who were considered flight risks or had tried to escape were even forced to sleep in cages. They had no means or opportunity to contact their families or authorities. Following the story, more than 2,000 enslaved fishermen were rescued and transported back to their home countries over a six-month period and at least one fishing company was shut down.

Exposing the issue

Lisa Rende Taylor, founder and executive director of Project Issara, a Bangkok-based agency that focuses on slavery in south-east Asia, says that recent media attention and companies flexing their muscles with suppliers have led to more enslaved workers being released. Project Issara (which means freedom in several south-east Asian languages) uses a multi-lingual migrant worker hotline to try to reach enslaved people in Thailand’s fishing industry, as well as those forced into working in the sex industry, in factories and on farms. “The vast majority of our work has been in the Thai fishing industry,” she says.

Among the reasons slave labour is so extensive in Thailand is the nation’s rapid recent development, which has led to a need for low-skilled and no-skilled labour, Taylor says, and many Thai citizens do not want those jobs. “Migrant workers play a very important role in the Thai economy,” Taylor says. The country has about 4 million migrant workers, most undocumented, and Thailand lacks a system to move them into jobs safely and legally, so there is no way to register them. Since they are undocumented, brokers charge them fees and often keep possession of their identification documents. “All the costs get put on them, the debt is ongoing, they are forced to work overtime and they are watched by controllers and brokers,” Taylor says.

For those workers fortunate to be released from bondage, many face new challenges of recovering their health and finding new jobs. In Thailand, all workers can pursue back wages, says Taylor. Some of the former fishing boat workers have been able to get jobs with some of Project Issara’s business suppliers, which enable them to get paid and have a place to live while awaiting compensation.

One company shaken by revelations of slavery in Thailand’s fishing industry, Santa Monica Seafood, an independent importer based in Rancho Dominguez, California, has plans to work with an NGO to improve its ability to root out slavery in its supply chain. “We need the help of a third party with experience in this area,” says Logan Kock, vice-president for responsible sourcing. “It has to be a real earnest attempt. We need to do something substantial.” The company buys a lot of its products from south-east Asia, including squid and shrimp from Thailand.

“We do audit plants and have others that audit plants for us, but we need to be more proactive and get more verifications,” Kock says. “We can’t confirm that any of our products come from slave labour – but now we have a real good illustration that this problem exists. We want to make sure what we’re doing is right and that we can influence governments, NGOs and others to eliminate this. We want to shore up our supply chain and influence others where we can to avoid it.”

Nestlé, another company that receives seafood through the Thai fishing industry for some of its products such as pet food, is also stepping up investigations into its supply chains. “Our mandatory Nestlé Supplier Code and Responsible Sourcing Guideline on Fish and Seafood require all of our suppliers to respect human rights and to comply with all applicable labour laws,” says Lydia Méziani, senior spokeswoman for Nestlé. Over the past year months, the company has been working with the supply chain consultancy Achilles to better understand its supply chain in the Thai seafood industry. Nestlé’s NGO partner Verité has collected information from fishing vessels, mills and farms in Thailand and from ports across south-east Asia to identify where and why forced labour and human rights abuses may be taking place. “We will publish Verité’s key findings alongside a time-bound action plan to address the issues identified in the fourth quarter of 2015,” says Méziani.

In addition, Nestlé is working with suppliers and other organisations in the Thai seafood trade to share its findings and to decide on a course of action. “Nestlé is also is participating in a multi-stakeholder International Labour Organisation Working Group, consisting of representatives from the government of Thailand, local seafood suppliers, and international buyers,” Méziani says. “This group has developed training guidelines for factories, primary processors and fish farms to help end unfair practices, and tools to support the inspection of fishing vessels to identify where forced and child labour is taking place.”

Cocoa farms

An area that has drawn increased international scrutiny and also involves Nestlé is the cocoa industry in western Africa, particularly Ivory Coast, which produces about 40% of the world’s cocoa. Young boys often are forced to work on cocoa plantations, using machetes and dangerous pesticides and carrying extremely heavy loads.

“Nestlé has committed to investing 110 million francs [£75m] from 2009 to 2019 to enable farmers to run profitable farms; improve social conditions; and source good quality, sustainable cocoa for our products,” says Méziani. “In 2014, it established the Child Labour Remediation and Monitoring System (CLRMS) in Ivory Coast, to help us and our partners identify children at risk in each cocoa community and the specific conditions that put them at risk.”

The company and its partners also work with individual households and the community to raise awareness and prevent child labour. CLMRS has been introduced in 22 farmer cooperatives and will be rolled out to all Nestlé Cocoa Plan cooperatives, of which there are around 70, by the end of 2016, Méziani adds. In 2014, the company refurnished or built 17 schools in Ivory Coast, enabling 2,908 children to go to school for the first time.

Anti-slavery organisations agree that while identifying slavery in a supply chain is difficult, the best way to eliminate forced labour is to get businesses directly involved, so suppliers know the issue is being taken seriously. “Through their purchasing power, companies can have critical impact in reducing worker exploitation in the suppliers from which they buy raw materials, products and services,” says the Walk Free Foundation’s Dafalia. “This buying power represents an opportunity to leverage their influence with the companies they do business with and in the countries they operate in.”

One of the biggest challenges is the complicated nature of supply chains, says Sobik. “Companies sometimes are not aware of what’s going on in areas where they buy materials.” Severe abuses tend to happen several tiers down the supply chain in areas where companies have little contact. “The fishmeal collected in Thai boats, the mica powder dug by children contained in our make-up, are all at the bottom of supply chains,” Dafalia notes. “But modern slavery taints products we buy and use every day and it’s not impossible to reduce its incidence.”

Project Issara’s Taylor adds: “Being able to engage global corporations is the most effective way. In trying to drive change on the ground, corporations work best. Once you look at everything in the supply chain, you have another actor there with serious leverage. Another effective approach is putting business systems in place to address forced labour risks, ensure workers can maintain documents and prevent debt from happening.”

Some businesses have been surprised to find forced labour in their supply chains, saying their factories have been audited numerous times and auditors did not find problems. “But most auditors don’t talk to employees,” Taylor says. “The majority of places where we’ve found forced labour and child labour had been audited many times.” After forced labour has been identified, Project Issara works with the factory owners to eliminate the risk of hiring forced labour and try to compensate workers.

Cutting off a supplier also may not be the best choice. “To be the most effective, you have to take the right action,” says Kock. “It’s not a situation where you can just get out; then you no longer have leverage. If you do that, you’re taking all your controls out of it and giving it to someone else.”

Businesses and consumers must collaborate with governments to ensure that existing anti-slavery laws are enforced and stricter laws implemented. “Without the critical action of us all, slavery will continue to exist,” says Dafalia. “The role of businesses is paramount – without a strong commitment to clean up their supply chains, we cannot tackle this crime. Governments are paramount. They need to crack down on criminals through strong law enforcement and ensure victims are treated justly and receive the proper support. We as consumers have the power to hold governments and businesses to account over their actions to end slavery.”

Anti-slavery tools

Several organisations have developed toolkits for companies to use to identify and prevent forced labour in their supply chains. The Walk Free Foundation has a guide to how companies can assess and remedy the risks inherent in their supply chains. “For instance, companies can introduce anti-slavery criteria in procurement decision-making,” says Gina Dafalia, head of communications. “They could conduct systematic due diligence and risk assessments by asking their suppliers about risk factors in their work force. They can do on-site investigations that can provide them with the enhanced visibility and transparency on the ways in which they are avoiding causing or contributing to modern slavery.”

The Tronie Foundation has established a Freedom Seal for companies that thoroughly review their supply chains and related systems and agree to comply and require all their suppliers to comply with anti-trafficking laws. Companies must complete an application and provide documentation of their findings. Several companies are in the process of completing the application, says Paul Hirose, CSR advisor to the Tronie Foundation, and one company has been awarded a Freedom Seal. Businesses can use the seal to show they are fighting slavery in their operations and supply chains, which appeals to consumers, Hirose says.

“Customers would rather purchase from companies who do not have slaves in their supply chains and they will patronise the Freedom Seal companies,” he says. “Losing market share will incentivise other companies to clean up their supply chains.”

slavery slave labour modern slavery fair wages slavery briefing supply chain