Companies are looking to move beyond niche green products to system-level change. Internal indexes are becoming the favourite tool for making that happen

Euro 2012 may be over, but the planet is still counting the cost. Big tournaments spark big kit sales. Kids understandably want shirts emblazoned with the names of their favourite footballer, but that means more fabric, more water, more energy, and more resource-use generally.

Nike reckons it has a solution. The US sports brand recently introduced national team kits made almost entirely from recycled polyester. Shorts and shirt together comprise 13 recycled plastic bottles. That’s 16m recycled bottles in all for last year’s kit.

The example is one of a range of sustainable designs to have emerged from Nike’s labs of late. Flyknit is another. Instead of using multiple materials to make a shoe upper, the company has come up with a process that keeps it to just one. The result is a lighter shoe, and a lot less waste.

Such eco-innovations don’t appear out of nowhere, says Nike’s Hannah Jones. Her job title is a clue to just how central sustainability thinking is becoming at the company: vice-president for sustainable business and innovation.

“We run our entire sustainability approach in the same way as we think about innovation,” she says. “What we’re doing is taking key parts of the business and thinking how you rewire them to include sustainability in their strategy, in their innovation agenda and in the roll-out of how they work.”

Sustainable by design

Rewiring can fast turn into a jumbled affair, however. Hence, Nike’s development of the pioneering considered design index. Launched six years ago, the index lays out a range of sustainability criteria for product designers. (See box.)

The results have been solid, if not spectacular. The adhesive-free Considered Boot and the hi-tech Air Jordan XXIII baseball shoe made with recycled rubber are two early innovations.

About one-sixth (17%) of seasonal footwear products now meets the baseline “considered” standard, according to Nike’s most recent figures. The baseline does not make them part of the considered line, but their scoring helps designers understand and assess a starting point for that product.

Integrating sustainability into product design takes time, Jones argues. Each “stage gate” of product development needs to be examined through a sustainability lens.

For that reason, Nike has just launched the sourcing and manufacturing sustainability index. The internal ranking system rates supplier factories according to labour conditions, health and safety standards, and environmental performance.

The index, which rolls up into the more comprehensive Nike manufacturing index, seeks to elevate sustainability concerns alongside traditional supply chain measures of quality, cost and on-time delivery.

Nike’s goal is to merge these indexes eventually, thereby moving the company’s whole production chain onto a more sustainable footing.

Jones points out: “Ultimately what you want is sustainable products made in sustainable, best-of-class factories.”

Beyond risk assessment

Another company pursing a similar strategy is the US domestic products manufacturer SC Johnson. As far back as 2001, the company introduced an internal system to rank the environmental profile of product materials.

The Greenlist index seeks to move beyond “mere risk assessment” and instead optimise product sustainability, says Cindy Drucker, SC Johnson’s director of global sustainability.

Following a complex calculation process, every material is given a rating of between zero (worst) and three (best). The lowest category can only be used when there is no viable alternative, and only then with senior management sign-off.

“[Product scientists] are required to look at increasing the ranking of the product each time it is reformulated,” Drucker says.

This goal of gradual improvement is paying off. When SC Johnson launched its Greenlist approach, fewer than one in five (18%) products were classified in the top two categories. Today, the proportion is more than half (51%).

By way of example, Drucker cites air freshener Glade Refresh Air. SC Johnson’s lab technicians switched from liquid petroleum gas to create the product’s spray, to compressed nitrogen. In so doing, they drastically cut the amount of volatile organic compounds produced.

Peter White, global sustainability director at US consumer goods company Procter & Gamble, admits that internal indexes are “not perfect”. Product innovation is a work-in-progress. In this context, indexes serve as pointers towards hoped-for solutions, rather than roadmaps to certain futures.

Most large companies have multiple schemes for encouraging more sustainable products. In as much as internal indexes can “pull all these threads together” and set a framework for decision-making, they can be hugely useful.

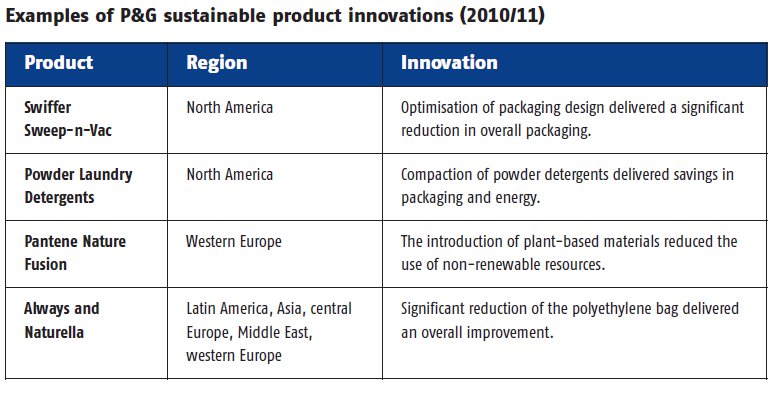

White speaks from experience. P&G launched its sustainable innovation products category five years ago. The approach seeks to generate a line of flagship products that have cut their environmental impact by 10%, without impinging on the product’s overall sustainability profile (see box).

P&G is seeking to derive revenue of $50bn from these flagship products between 2007 and 2012. With $40bn already generated, the company is on target.

Breadth over depth

Where internal indexes differ from more product-centric approaches is in their scope. Focus on single product lines, and you’ll get a few exceptional eco-products and a lot of dross. Set your sights on systems change, and a pan-portfolio improvement should be the result.

That’s certainly the vision of Marks & Spencer. The UK retailer is looking to integrate aspects (what it calls “attributes”) of its Plan A strategy into every single product over the coming years.

“What we want to avoid is creating a little eco ghetto where you’ve got a fantastic ethical range in the corner of your shop … but it’s a small proportion of what you sell,” says Mike Barry, head of sustainable business at M&S.

The company’s current objective is for all its food and clothing products to have at least one Plan A attribute by 2020. That could be Marine Stewardship Council certification in the case of fish, for example, or Fairtrade cotton in the case of T-shirts.

“What we’re trying to do with [Plan A] attributes is drive ownership across the business so that every commercial part of the business thinks Plan A, and has an action plan to build Plan A into its product mix,” says Barry.

He concedes that the approach prioritises breath over depth. The idea is for individual product lines to accrue sustainability components over time. It’s not a licence for the next breakthrough idea, but the cumulative impact is arguably more significant than an isolated case of innovation.

Already, almost one-third (31%) of the almost one billion food and clothing items that M&S sells each year have a Plan A attribute, according to the retailer’s recent How We Do Business report.

That’s not to say innovation is no longer on the cards. M&S sets an action plan for each product category area. Senior managers are then incentivised through their performance evaluations to meet ever more exacting sustainability criteria.

Barry has a piece of advice: if you want innovation to happen, avoid “micro-managing”. Managers should set a vision, provide some parameters and provide rewards for high performance. The nuts and bolts should be left to product developers themselves.

Standardisation

Internal indexes undoubtedly act as a handy instrument for in-house innovation. If their impact is to be felt outside the company, however, then they must be shared with suppliers. Nike, SC Johnson and P&G are all committed to that process.

Ultimately, they must be shared with industry competitors too. Work is currently under way at the Sustainability Consortium to agree some universal, rather than company-specific, definitions of sustainable products.

Such moves are welcome, according to Stephanie Draper, director of change and system innovation at Forum for the Future. Internal indexes are helpful as a “vehicle for asking different questions” of a product, she concedes.

“Yet what we’d like to see over time is some standardisation of these indexes so we can compare products.”

Considered index

Nike’s considered index is a systems-integrated, online tool for evaluating the predicted environmental footprint of a product before commercialisation.

The system examines the largest environmental impacts for Nike products, primarily in the areas of waste and the use of materials, energy and solvents. The index metrics are based on more than a decade of collecting product-related data. Products are assigned a “considered” score using the index framework based on Nike’s known footprint in these areas.

Only products whose score is significantly better than the corporate average can be designated as “considered”. Nike has recently introduced specific considered footwear and apparel indexes. Its goal is to have all footwear products and apparel products reach 100% “baseline” standard by 2015.

Examples of P&G sustainable product innovations (2010/11)

- Nike’s Considered Design Index

- SC Johnson’s Greenlist

- P&G’s Sustainable Product Innovations

- M&S’s Plan A