The world’s first zero-carbon brewery in Austria demonstrates the brewer’s progress on slashing CO2 emissions, but water issues are trickier to tackle

The small town of Göss in Austria, about two hours’ drive from Vienna, seems an unlikely location for a green revolution.

It’s certainly green enough, as you would expect from an Austrian town. But its green credentials in the environmental sense are less obvious – not least because their source is the town’s brewery. The Gösser brand is Austria’s most popular beer and Göss is its spiritual home: beer has been brewed here since 960AD and the present-day brewery has been quenching Austrian thirsts since 1860.

Today, though, it is using a range of technologies and techniques to become the world’s first large-scale zero-carbon brewery. The facility, which produces 1.4m bottles of beer a day, has cut its CO2 emissions from about 3,000 tonnes a year to zero thanks to the passion and persistence of its brew master, Andreas Werner, in a process that started in 2003.

The brewery had a head start because all of its electricity comes from hydro-electric power, which provides about two-thirds of Austria’s power needs. But electricity is not the only energy issue for beer makers – brewing is a process that uses a lot of heat. Around half of the Göss brewery’s energy requirements come in the form of heat, and Werner saw an opportunity to procure a sustainable source of heat from a nearby sawmill, which is just a few hundred metres away.

Waste not, want not

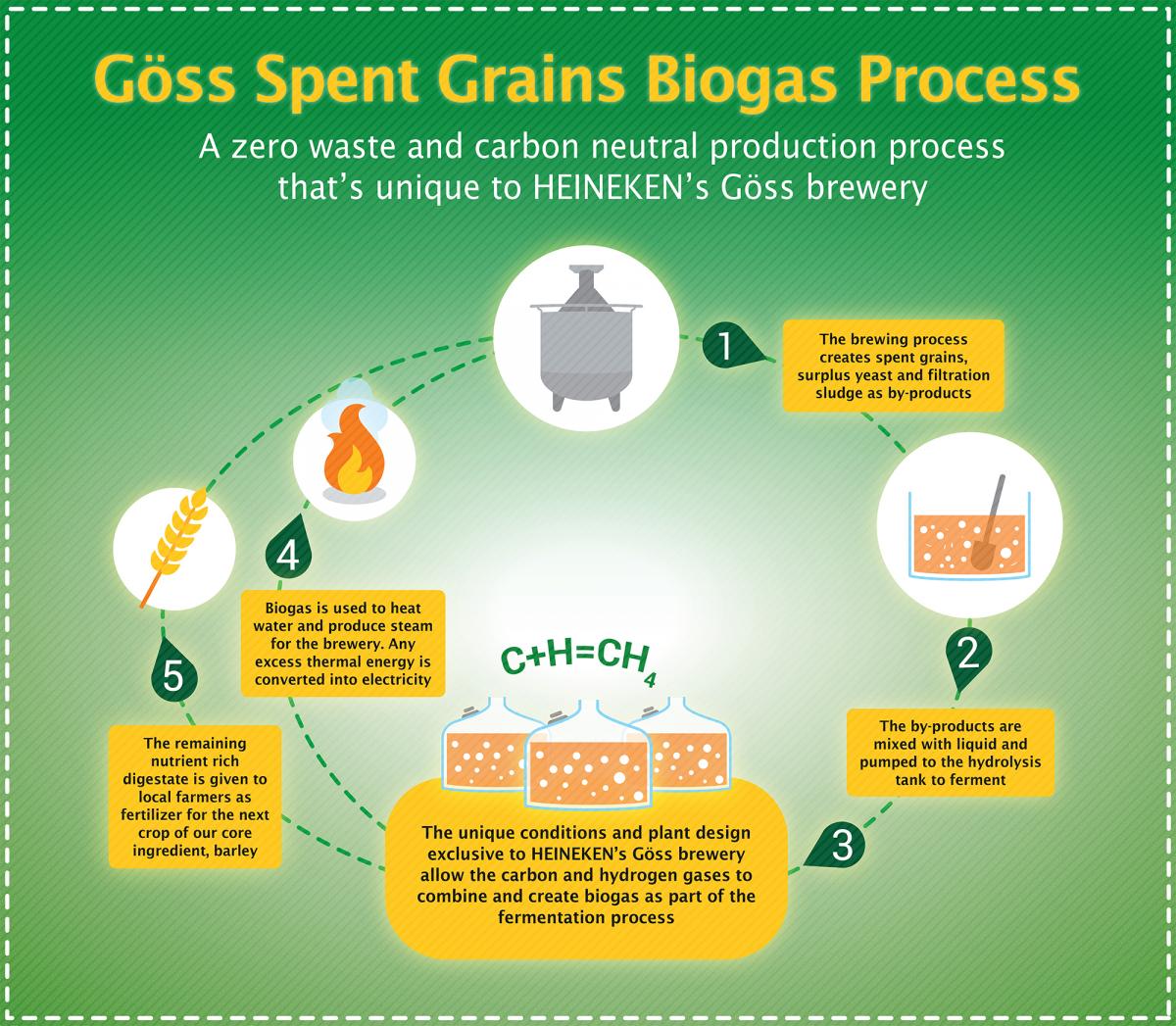

Some 40% of the brewery’s heat is now provided by the mill’s waste heat. Another 10% comes from recovering the facility’s own waste heat and 3-5% comes from a solar thermal plant on the brewery’s disused football pitch. The rest comes from a newly installed anaerobic digestion plant that uses the spent grain from the brewing process. This used to be sold to local farmers as animal feed but now is used to create biogas, which is then burnt in a combined heat and power (CHP) plant to provide thermal and electrical energy to the brewery. The residue of this process, the digestate, is sold as a fertiliser.

“It is great that we are zero-carbon but it has not been easy,” says Werner. “On the supply side, we are getting different types of energy from different processes and we have different demand at different times. This complexity is one of the challenges of going green.”

Brewing may not seem to be an obvious industry to lead efforts to cut greenhouse gases (GHGs), but the investor group Ceres points out that the effects of climate change are beginning to threaten the industry.

Warmer temperatures and extreme weather events are harming the production of hops, a critical ingredient of beer, and clean water resources are also becoming scarcer. “That's why leading breweries are finding innovative ways to integrate sustainability into their business practices and finding economic opportunity through investing in renewable energy, energy efficiency, water efficiency, waste recapture, and sustainable sourcing,” Ceres says.

The story of the Gösser brewery would be little more than an inspiring clean energy case study except for one thing – it is owned by Heineken, one of the world’s largest brewers. The Dutch company sees Göss as a flagship not just for its efforts to become more environmentally sustainable but also to incorporate sustainability into its business agenda, says Michael Dickstein, global director of sustainable development.

Role model

“What we have here is a great role model for how you can connect one story of best practice to many different parts of the business around the world and connect the sustainability agenda in a very effective way to the business agenda,” says Dickstein. “What’s happening at Göss is about risk mitigation, eco-efficiency and commercial opportunities.”

It is also part of a company-wide target to cut GHG emissions by 40% from 2008 levels by 2020. Of course not every brewery has access to cheap hydro-electric power or a nearby sawmill with waste heat to spare. However, other Heineken brands are in sunnier climes and are making extensive use of solar power.

Brands such as Tiger in Singapore, Birra Moretti in Italy and the Netherlands’ Wiekse get all of the electricity for their operations from solar power, allowing Heineken to market them under the tagline “brewed by the sun” – another example, says Dickstein, of a move that boosts both the sustainability agenda and Heineken’s brand image.

“The guiding principle is that if you want to make sustainability itself sustainable, you need to link it closely to business objectives,” he says. For clean energy projects, the low oil price has made that more difficult, although that has been balanced out by the strength of the climate change agreement reached at last year’s COP 21 Paris meeting.

“Last year it was really difficult to marry the short-term business case and the long-term sustainable business case because of the low oil price,” Dickstein says. “But COP 21 helped because it became clear that the national plans required targets that implied an even bigger shift towards renewable energy.”

But it is vital to have the infrastructure in place. Dickstein points to the contradiction of having 4,000 solar panels on its brewery in Tadcaster, Yorkshire, and more than 3,000 at Den Bosch in the Netherlands, cloudy northerly locations, while many of its breweries in sun-soaked Africa have no solar panels. “You would think [solar] would be a no-brainer [in Africa], but too many countries lack grids with the reliability to make this viable,” Dickstein says.

Thirsty work

For brewers, water is an even bigger sustainability issue than energy, since more than 95% of every glass of beer consists of water. Brewers and other alcohol producers are one of the more advanced sectors in dealing with this issue, says Cate Lamb, head of the water programme at CDP, which helps companies quantify and report their environmental impacts.

“It’s because water is absolutely fundamental to the business model, not just in their own facilities but in the production of their raw materials such as grain,” Lamb says. “And many business models are built on the assumption that there will be a stable, high-quality supply of water available. This is an assumption that can no longer be guaranteed. There is increasing competition for an incredibly finite resource for which there is no alternative. That creates significant physical, regulatory and reputational risks.”

Heineken is trying to cut its use of water wherever it can, and has reduced the amount of water per litre of beer across the company from five litres to 3.9 litres in just two years. “This is a key focus area for us,” says Dickstein. “We make sure our wastewater goes through either our own treatment plants or local treatment plants wherever possible. For the 15 breweries where that currently doesn’t happen we will have found solutions by 2020 so we are fully compliant on our wastewater targets everywhere in the world.”

The company has also commissioned a comprehensive risk assessment from WWF that has identified 23 breweries (out of a total of 160) that are in water-scarce areas. “Later this year, we will probably add a couple more to that list. Water scarcity is becoming more and more of an issue,” Dickstein says.

Water challenges

Making the case for water conservation on a straightforward economic basis is more difficult than for energy because water – as a result of its fundamental importance to life – is generally priced below its true value. However, brewers in particular have little choice but to act. And while a company can cut energy emissions significantly by focusing on its own operations, it is much more exposed to external factors when it comes to water.

“Worsening water security is often beyond companies’ control and linked to how water is managed in the area where they operate,” says Lamb. “You can be the most efficient user of water in your own operations but if it is being over-abstracted or polluted by other users your supplies are at risk.”

In 2015, for the first time, CDP ranked companies on their performance in dealing with water issues and only one brewer received an A ranking – Japan’s Asahi. Where it stood out in comparison to the rest of the sector was in the quality and comprehensiveness of the water risk assessment it undertook, Lamb says.

“If you want to understand your risks, you have to do more than map your facilities on a water stress map,” she says. “You need to be talking to water utilities – and about more than how much your bill is. You need to know what their reserves are like, what they’re doing to adapt to climate change – those sorts of things. Not enough companies in the sector are having those types of dialogues.”

Asahi also stood out in reporting that the results of its water risk assessment would be used to inform its business growth strategy and in its supply chain management, CDP says.

Dickstein acknowledges that Heineken cannot resolve water issues alone. He says: “We are trying to build water stewardship into planning how much water we take out of a watershed but we know we can’t resolve these issues on our own. We need a more comprehensive approach. We need the local authorities and the private sector to contribute to solutions.”

Savings all round?

The water issue also illustrates how different challenges affect each other – for better and for worse. SABMiller pointed out in its submission to the CDP that its efforts since 2010 to reduce water intensity had the impact of reducing CO2 emissions, as the processing and treatment of water requires energy. It also led to cost savings. “Within our cost savings programmes [water and CO2 combined], we saved $117m in 2014/2015 [compared with 2010] from water- and energy-related initiatives.”

Heineken, on the other hand, came to this agenda somewhat later and has had to invest in building water treatment plants at some breweries, which has actually increased its energy use, Lamb says. It has had to choose which is more important – cutting energy use or water use. “In water-scarce areas, water reduction will prevail,” Heineken told CDP.

Like many brewers, Heineken prides itself on its local sourcing of ingredients, which is a powerful branding tool. While many other food and drinks groups are switching suppliers from water-stressed areas, brewers are not keen to do so. “In some water-scarce areas, it is from a water resources perspective preferable to import agri-commodities like barley [and] corn,” Heineken reported. “However, local sourcing supports the local economy and provides a source of income for local communities. Local sourcing will prevail [over saving water].”

Heineken’s efforts in Austria “demonstrate what is possible through working creatively with the local landscape and stakeholders,” says Jenny Lopez, sustainability adviser on food and energy at Forum for the Future. “What I hope to see next is that Heineken develop their strategy further to ensure that zero-carbon examples like this do not become standalone case studies, but are being scaled up as part of a global implementation plan.”

Real sustainability leadership is shown when companies are willing to open up these bigger questions and take actions that go beyond their business, to the world they’re operating in, Lopez adds. “It is about the company thinking long-term to understand and redefine how sustainability issues are material to their business, and how this fits within the company’s long-term strategy and vision.”

climate CO2 emissions Environment zero-carbon Heinenken renewable energy water management