Comment: Private sector investment has helped results-based finance rocket from $500m in 2014 to $8.8bn last year. But David Kinley, author of a new book on international finance and human rights, argues that it would take a lot for the halo effect to reach the entire market

Like children ushering spring into The Selfish Giant’s wintery garden, there is now a small corner of the bond market that has more in common with Oscar Wilde’s morality tale than with former Bill Clinton aide James Carville’s quip that if he was ever reincarnated he’d want to come back as the bond market because “you can intimidate everybody”.

Social bonds (SBs), recently born and on the rise, are designed to achieve socially responsible goals and deliver healthy returns for investors at the same time. Noble aspirations to be sure, though one might justifiably ask why is that not the mission statement of all bonds? Springtime for the whole garden? Well, maybe.

As a means for government and corporations to raise funds, bonds are indeed a handy device. Bond issuers promise to pay back bond purchasers the amount they paid for them plus interest at some future predetermined date. Bonds are attractive to investors not only because they provide a fixed income but also because they are both tradable and usually low risk.

For SBs the goals of the funded activity are at least as important as the return on the investment

It is these appealing features that normally occupy the minds of bond holders. What precisely the funds raised by the bond issue are to be used for is of little or no concern. It is here that SBs make their mark. For SBs the goals and outcomes of the funded activity are at least as important as the return on the investment; ruminations on risk are, accordingly, apportioned equally across social outcomes and financial risk.

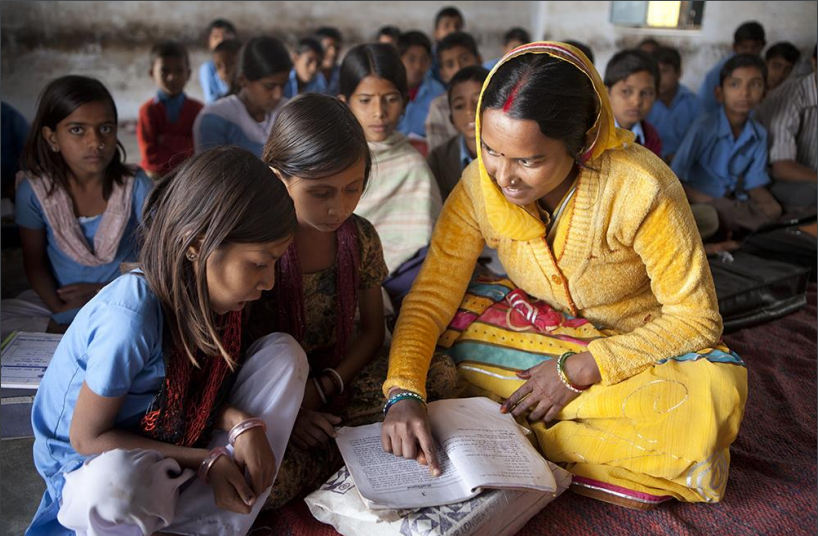

This “results-based financing” targets all sorts of welfare matters. From combatting recidivism in criminal juvenile justice systems in the UK and Massachusetts, to providing affordable housing in Canada and the Netherlands, to instituting mobile money platforms catering for women entrepreneurs in Kenya, and improving the safety and security of dairy produce storage and transportation in Pakistan.

Typically the guarantors have been governments either working at home when issuing social impact bonds, or overseas through aid-based development impact bonds. But private sector finance has now also joined the scene. Recent figures from the International Capital Market Association show that of the $8.8bn worth of SBs issued globally in 2017, private sector issuers accounted for some $1.3bn (or nearly 15%). They had been non-existent the year before. The whole SB market, though still tiny, has exploded out of the blocks, expanding 17-fold from its negligible base of $500m in 2014.

The private sector is here following the profitable path it took with SBs’ older sibling, environmentally friendly green bonds (Apple, for example, has issued more than $2.5bn worth of green bonds since 2016, allowing it to fund sustainability goals).

For the big end of town this is potentially a corner-turning moment

This is significant not just because it reflects private sector appetite for social or green bonds, it also underlines the fact that profit and social benefits are not mutually exclusive. Some, like Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock (the world’s largest asset holder), go further, stressing the essential need for business leaders to advance the “prosperity and security of their fellow citizens”, as well as their own profits. For the big end of town this is potentially a corner-turning moment, leaving behind the perception that it always costs to do good.

There are some grounds for optimism. Global Impact Investing Network’s (GIIN) latest annual survey of its 208 financial institution members underlines the hard-nosed financial expectations of GIIN’s membership. Two thirds of the likes of Credit Suisse, Deutsche Bank and JP Morgan, as well as the Ford, Gates and Rockefeller foundations, expect their social and environmental impact investments to at least match market returns.

And they’ve not been disappointed. According to GIIN, 76% of portfolios perform to that level, and 15% exceed it. Its data for achieving the social impacts themselves are even better – 79% performing to expected levels, and 20% outperforming them.

However, so much hinges on how these results are measured. Evaluating increases in levels of freedom, welfare and security – as the SBs strive for – is notoriously difficult. Even well-intentioned social investment initiatives tend to allow ambition to get ahead of capacity in this regard.

The EU’s new Action Plan for Financing Sustainable Growth, for example, has been criticised for not taking human rights seriously. In an open letter to European Commission President, Jean-Claude Juncker, a coalition of NGOs skewers the action plan for failing to “include human rights expertise” in its processes for measuring the social objectives of sustainable growth.

Other social bond programmes, like that of the International Finance Corporation (the private sector arm of the World Bank), use the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as their metric, but these too suffer from overreach. The 17 SDGs – which include ending poverty and hunger, advancing equality, health, education and decent jobs, and promoting a clean environment, economic growth, peace and justice – are supplemented by no less than 169 targets and 230 indicators. It's one thing pledging “to save the world”; another measuring progress in doing so.

What is clear is that social investing has made its mark in the bond market

True the Social Bond Principles, launched last year by the International Capital Market Association, are designed to encourage “transparency, disclosure and integrity in the development of the SB market”, but it is still too early to tell if they will.

What is clear is that social investing has made its mark in the bond market, with no fewer than 17 different funding structures now being traded in the asset class, including bonds, equity, debt swaps, guarantees and performance-based contracts. Whether this sprinkling of springtime blossom is enough to keep the intimidatory predilections of the bond market on the right side of responsible, however, remains to be seen. For the moment a socially responsible bond market remains more fable than fact.

David Kinley is Professor of Human Rights Law at Sydney University and a member of Doughty Street Chambers in London. He is author of 'Necessary Evil: How to Fix Finance by Saving Human Rights', published by Oxford University Press in May 2018.

David will be speaking about his book at an event hosted by the Business and Human Rights Resource Centre at Herbert Smith Freehills’ London offices on 9 July - for details see here.