Canada's world-leading single framework to price carbon takes effect next year, after strenuous efforts to win agreement from most provinces. But he faces huge challenges ahead

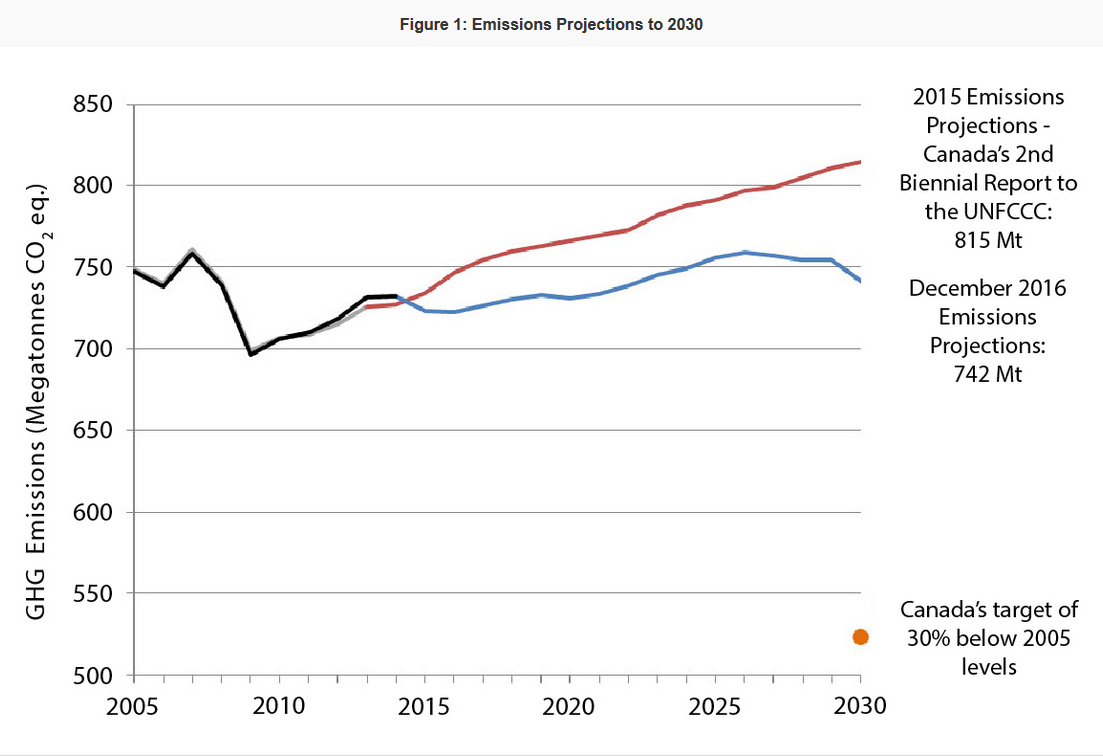

Canada is approaching go-time for an ambitious national plan to lower greenhouse gas emissions by pricing carbon. The Pan Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change (PCF), which Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party ushered in last December, takes effect in January, at its centrepiece a $10 per ton carbon tax that will attempt to lower Canada’s carbon emissions 30% from its 2005 levels, its Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement. The PCF also seeks to set a clean fuel standard, and cut oil and gas sector methane emissions at least 40% by 2025.

The PCF capped off a first year in office, during which Trudeau’s government put a five-year moratorium on new oil and gas drilling permits in the Arctic, in conjunction with Barack Obama’s outgoing administration; approved two large hydroelectric projects; funded a transcontinental highway electric car recharging project; and announced plans to end Canada coal-generated electricity by 2030. The latter goal will be helped by this month’s agreement to cooperate with the UK, which aims to phase out coal by 2025, signed during Theresa May’s visit to Ottawa.

Ontario and Quebec had already linked their cap and trade programmes with California, creating the largest system in North America

With the third round of the North America Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) negotiations beginning this month, Trudeau has said that Canada wants climate change, GHG reductions and a shift to clean energy to be written into the deal (see Trudeau goes head to head with Trump on climate in trade talks).

Under the PCF, Canadian provinces have until the start of 2018 to develop their own carbon tax or emissions trading system, the two main types of carbon pricing, at a minimum price of $10 per ton in 2018, rising to $50 per ton by 2022. If provinces don’t come up with their own scheme, the federal government will levy its tax.

“It [the PCF] was a massive step that had to happen here and it was a really, really important turning point for Canada to start our transition to a lower-carbon economy,” said Andrea Moffat vice president of the Ivey Foundation, which focuses on integrating the economy and the environment. “Just putting a price [on carbon] forces the conversation. It’s the recognition that carbon is an economic issue, not just environmental.”

In the decade-long era of Stephen Harper’s conservative government from 2006-15, Canada pulled out of the Kyoto climate agreement, leaving the country with a patchwork of subnational and disparate climate mitigation plans at the provincial level. British Columbia, for example, established the continent’s first carbon tax, now at $30 per ton, nearly a decade ago. At that same time, Alberta started requiring large emitters (over 100,000 tons annually) to lower GHG emissions 12% every three years, giving them the option of either trading or offsetting credits, or paying into a tax fund. Earlier this year, Alberta also implemented a carbon tax on transportation and heating fuel emissions, which will cost $30 per ton in 2018. (The mandatory PCF tax will mimic Alberta’s).

On the other side of the country, Ontario and Quebec linked their existing cap and trade programmes with that of California, creating the largest system in North America. Both will price carbon at roughly $19.40 per ton by 2020.

Canada’s clean technology sector now ranks fourth in the world and first in the G20, according to the 2017 Global Cleantech Innovation Index

The various provincial programmes and federal pricing actions now “must ultimately coordinate, harmonise and stitch together to achieve Canada’s NDC,” said Katie Sullivan, managing director of the International Emissions Trading Association (IETA).

As such, carbon pricing, although the most prominent feature of the PCF, is only one part of the equation. The other three core PCF goals are a phase-out of coal, mandatory methane reduction and a national fuel standard. What the PCF has done is to force every province to develop a real plan, with a back-stop carbon price ensuring that something gets done. An IETA chart shows many of the western provinces adopting some sort of carbon levy like BC and Alberta, and the eastern half cap and trade programs, like Quebec and Ontario.

While Sullivan says progress on the PFC has been “remarkable”, she adds that there are many challenges ahead of “a clear coast-to-coast approach – one that… enables business to understand compliance rules and clean investment opportunities over the long-term.”

To bring all provinces and territories into line, the PCF created a council of provincial environment ministers to model a unified climate scenario and pricing, and to work on reporting verification, so that a ton emitted in BC is the same as one verified in Newfoundland, and a national offsets programme.

The complementary measures to the federal carbon price will drive down GHG emissions reductions in ways that are “more relevant to certain provinces depending on the emissions profile,” said Moffat. She gives as an example Alberta’s methane-reduction policy, which aims to cut emissions from the oil and gas sector by 45% by 2025.

In Alberta big reductions will come from phasing out coal, and in BC it will be from clean electricity regulations and a low-carbon fuel standard

Indeed, beyond carbon taxes or cap and trade schemes, many provinces had already taken measures to lower GHG emissions before the PCF, including permanently banning coal-fired electricity generation (Ontario, 2014), and targeting some 100,000 electric vehicles on the road in 2020 and 1 million by 2030 (Quebec). The east coast province of Nova Scotia requires utilities to reduce emissions by 55% by 2030, and mandated 40% of provincial electricity be renewably sourced by 2020; Prince Edward Island is second only to Denmark in wind energy penetration, supplying 25% of the island’s total electricity requirements, and the Muskrat Falls hydroelectric project in Newfoundland and Labrador will result in 98% of the province’s electrical consumption met by renewable energy by 2020.

Clean tech leader

Canada’s clean technology sector now ranks fourth in the world and first in the G20, according to the 2017 Global Cleantech Innovation Index (GCII). It climbed from seventh place in 2014 by tripling its amount and value of such funds, as well as the number of domestic investors in it.

A Smart Prosperity Institute report noted that Canadian entities in 2016 had issued some C$32.9bn (USD$26.9) in climate-aligned bonds (C$2.9bn labelled as green bonds), making it the fifth largest country of issuance.

Under the PCF, some provinces will reinvest carbon pricing revenues into clean energy technology, others will use them to reduce taxes and will need “other financing options for clean innovation, green infrastructure and clean energy,” said Mike Wilson, executive director of the Smart Prosperity Institute, a think tank based at the University of Ottawa that advances market solutions for a cleaner economy.

However, the shift to clean energy does not come without a price: Nova Scotia’s electricity prices have risen 62% since 2005 and are currently the highest in the country. Studies have shown that the shift to clean energy will continue to drive up costs for businesses and households alike. A report by business think-tank the Conference Board of Canada, shows that if the carbon price rose to $80 per ton by 2025, the overall economy would reduce by 1.8% and average weekly Canadian wages by 0.8%.

Canada’s clean technology sector now ranks fourth in the world and first in the G20

Saskatchewan and Manitoba refused to sign the Pan Canadian Framework, and as such won’t be eligible for the $2bn being made available to the provinces for new emissions-reducing projects under the Low Carbon Economy Fund as part of the plan – although Manitoba is planning to develop its own climate plan.

Dr. Mark Jaccard, professor of sustainable energy at Vancouver’s Simon Fraser University, says regional differences over tackling climate change are to be expected. “This is how humanity has been tackling climate change. It is unfortunately the only way we will make progress,” said Jaccard. “So to critique or even reject a national effort because of lack of a national consensus would be to deliberately make no effort.”

Marketing the plan will be critical. In a May Angus Reid Institute poll found that more than half of Canadians said they would prefer holding off on the carbon tax if it puts the economy at a disadvantage with the US. Only 44% of Canadians said they supported the carbon tax and a similar number, 43%, said their provincial government should fight the implementation of the carbon pricing plan. (A similar poll by the same think tank in 2015 found that some 75% of Canadians supported a cap and trade programme, and more than half a national or provincial carbon tax.).

Moffat believes that part of the problem is in the conversation. “When you talk about a transition it doesn’t mean you go from zero to 60,” she said. “To move forward, we have to move away from the polarising discussions, and we need to get good expertise to build the policy.”

Most importantly, she noted, Canada needs to set up transparent, non-partisan structures to ensure that GHG reductions policies don’t become a political “wedge” issue, subject to change with every election. “This is still a fragile thing to have this framework,” she said.

Only 44% of Canadians support the carbon tax, worried they will be at a disadvantage with the US

Other critics, while supporting pricing carbon and the ambition of the plan, see inherent problems in it. Dr David Layzell, director of the Canadian Energy Systems Analysis Research (CESAR) Initiative at the University of Calgary, sees the benefit in being able to use revenue from a carbon tax to invest in the transformation of anthropogenic systems, but doesn’t believe the PCF will reduce the demand for energy nor shift it to alternative sources – or at least not in the amount needed to make a real difference.

To do that, Canadian society would need to demand a total shift in fossil-based transportation to, for example, electric and autonomous driving vehicles. “Energy systems don’t change by artificially cutting off supply,” he said. “Virtually all changes in energy systems in the past are a result of demand-side changes.”

Wilson thinks the PCF is an “excellent start”, but believes the country needs to “ratchet up the price on carbon” beyond the C$50 (USD$41) in the PCF and invest more significantly in clean innovation. “Virtually all analysis shows if Canada is to meet 2030 and mid-century climate targets and become an environmentally sustainable economy, we need to do more,” he said.

An IETA discussion paper on Canada’s carbon pricing strongly advocates for cap and trade over a carbon levy because the former would allow for allowances, offsets and performance credits, including extra-nationally, which in turn would increase reductions.

“Canada, more than most countries… must import lower cost reductions and think strategically about how it channels international climate finance commitments with a view to benefits [including GHG reduction imports] to meet its ambitions 2030 target,” said Sullivan, noting that the Deep Decarbonization Pathways Project (DDPP) and other analytics forecast that Canada will not be able to meet its NDC “without cooperative approaches – meaning international transfer of lower-cost abatement units….”

But arguing over whether a carbon price, or levy, is preferable to a national cap and trade scheme misses the point, said Jaccard. GHG reduction plans should consider the economic and political cost per ton reduced, plus the total reduction achieved. That way, he said, “you trade-off between political acceptability and economic efficiency, instead of being singularly focused on just one or the other.”

Most important is flexibility: for example, while Alberta and BC both have carbon taxes, in Alberta big reductions will come from phasing out coal, and in BC it will be from clean electricity regulations and a low-carbon fuel standard.

“People who say carbon tax is better than cap-and-trade or vice versa are like people arguing about the optimal serving of wine on the Titanic. We should just get on with it,” said Jaccard, calling them equal choices. “Flexible regulations are far superior from a political acceptability perspective - and that is the most important with climate policies.”

Erin Flanagan, director of the federal policy programme at the Pembina Institute, a 30-year-old clean energy advocacy group, points out that the PCF still leaves Canada with an “ambition gap” of 44 million tonnes of CO2 that it will need to cut to meet its 2030 target – though this could be filled by extending the national carbon price another eight years from 2022 to 2030 when it is reviewed again in 2020.

Canada still has an ambition gap of 44 million tonnes of CO2 that it will need to cut to meet its 2030 target

The government is also not accounting for the impact of substantial investments in clean technology in the climate plan, including the $2bn announced in 2016 to establish the Low Carbon Economy Fund, and new clean fuel standard and heavy-duty vehicle retrofit rules to tackle transportation emissions, the largest and fastest growing source of emissions in many parts of the sparsely populated and far-flung country, particularly in Ontario and Quebec.

She says transport emissions will also be driven down through the creation of a new National Trade Corridors Fund, with $2bn in funding over the next 11 years to tackle freight bottlenecks and heavy congestion in cities like Toronto. The Pembina Institute is urging the federal government to work with Ontario and Quebec to develop North America’s first low-carbon highway, between Windsor and Quebec City.

Although the failure of all provinces to back PCF is a setback, she is optimistic that the country, branded a “climate criminal” by NGOs such as Greenpeace during the Turner years, is now on the right track. “Saskatchewan hasn’t signed on so it isn’t complete consensus,” she says. “But the PCF still represents the greatest consensus we’ve ever had on climate.”

This is part of an in-depth briefing on Canada and climate change. See also:

Trudeau brings Canada in from the cold on climate change

Can Alberta put a cap on the oil sands?

Canadian mining companies clean house in hopes of leading the green economy

Trudeau goes head to head with Trump on climate in trade talks

Resource firms try to learn lessons from Canada's troubled history with First Nations

IETA carbon price Arctic oil drilling Clean technology methane emissions oil and gas coal Pembina Institute Alberta oil sands Quebec electric cars