Major names are stepping up their green investments, with a switch to clean energy becoming perhaps the most popular – and most visible – long-term strategy for corporate carbon cutters

A host of multinational companies have signalled their intent to curb greenhouse gas emissions, and the knock-on effects will ripple through supply chains and clients, analysts say. In the past few months, the likes of Starbucks, Wal-Mart, Goldman Sachs and Johnson & Johnson have pledged to source all their energy from renewables. They have joined a list that already included Apple, Microsoft, Google and General Motors. Some of these are investing billions of dollars in their own clean energy installations.

Now the business world is looking to the COP21 negotiations on climate change in Paris, starting at the end of November, to deliver the underlying policy frameworks that will help support the shift. Emily Farnworth, campaign director of the Climate Group’s RE100 project, which works to help companies source 100% of their energy from renewables, says the growing adoption of renewable energy targets is motivated by considerations of future cost and energy security as much as by companies wanting to do their bit for climate action.

The steep drop in solar energy prices over the past few years – particularly in India, where parity with non-renewables has been achieved in many regions – has also driven take-up. And the reputational benefits of the switch must not be underestimated.

Since RE100 – run in partnership with CDP – was launched in the UK in November 2104, 40 companies have joined, including some of those named at the top of this article, and the campaign is now being rolled out in India and China as well as Europe and the US. Sectors range from telecommunications and retail to IT and food.

“The appetite for this is certainly growing – multiple factors are pushing companies to consider switching out of fossil fuels,” Farnworth says. “Many of them realise that a big part of their carbon output comes from electricity but also, more broadly, that this is where the world is moving. “It therefore becomes viable to make it part of their strategy in terms of cutting potential risks from rising carbon prices or uncertain supply in the years ahead.”

Some of these major players are also finding they have significant purchasing power for renewable energy, potentially unlocking secure, long-term pricing. A virtuous circle is forming, Farnworth says, in which the more high-profile names commit to renewable energy, the more credible and attractive the process becomes. “Obviously some of the big organisations we have on board at the moment have huge influence over their supply chains and clients,” Farnworth says. “It is setting an example and supporting others that are considering the switch.”

Banking on change

Goldman Sachs, for instance, which has pledged to almost quadruple its initial $40bn renewable energy investment, has stated its determination to push “environmental opportunities” among clients. Other major brands are taking their own steps to decentralise and de-carbonise their energy supplies. In late October, Apple and its biggest supplier, Foxconn, said they would build solar plants to produce more than 600MW of electricity, a step towards Apple’s goal of making the Chinese factories that produce the iPhone run on 100% renewable energy.

Two-thirds of that will come from Foxconn solar plants in Henan province, and the remainder from bases that Apple will build itself across China in order to offset the carbon in its supply chain in the region that mainly comes from coal. Apple says its Chinese operations are now carbon-neutral after the completion of a 40MW solar scheme in Sichuan province. Overall its plans would offset the equivalent of 4 million passenger vehicles a year by 2020.

Terry Gou, founder and chief executive of Foxconn, said: “I hope this renewable energy project will serve as a catalyst for continued efforts to promote a greener ecosystem in our industry and beyond.” Campaign group Greenpeace has welcomed the supply-chain plan and called on other technology companies to follow.

“We need governments and companies to transition us to renewable energy as rapidly as possible, and Apple’s announcement today is a major step forward in building a renewably powered supply chain for its products,” says Gary Cook, a Greenpeace IT analyst in the US. Samsung, Microsoft and other IT companies should follow Apple’s lead in “manufacturing their cutting-edge devices with a 21st-century energy supply”, he says.

Apple chief executive Tim Cook has been bold about using the company’s scale and resources to tackle climate change. This year, Apple struck an $850m deal with First Solar, a US developer, to supply clean electricity to its California headquarters, retail stores and a data centre over the next 25 years. Cook told an investor who challenged the economic rationale behind such investments that if they only considered financial returns, they should “get out of the stock”. But he added the First Solar deal should create significant savings, partly owing to US tax credits for green schemes.

Flexible approach

RE100 does not enforce specific deadlines for participants to be 100% renewable but many companies are aiming high. Johnson & Johnson aims to be 100% renewable by 2050, with CEO Alex Gorsky saying the company strives every day to improve energy efficiency and to get involved in green energy projects. Others setting targets include Goldman Sachs (100% renewable by 2020); Nike (100% by 2025) and Procter & Gamble (30% by 2020). US furniture company Steelcase, another recent joiner, became 100% renewable last year.

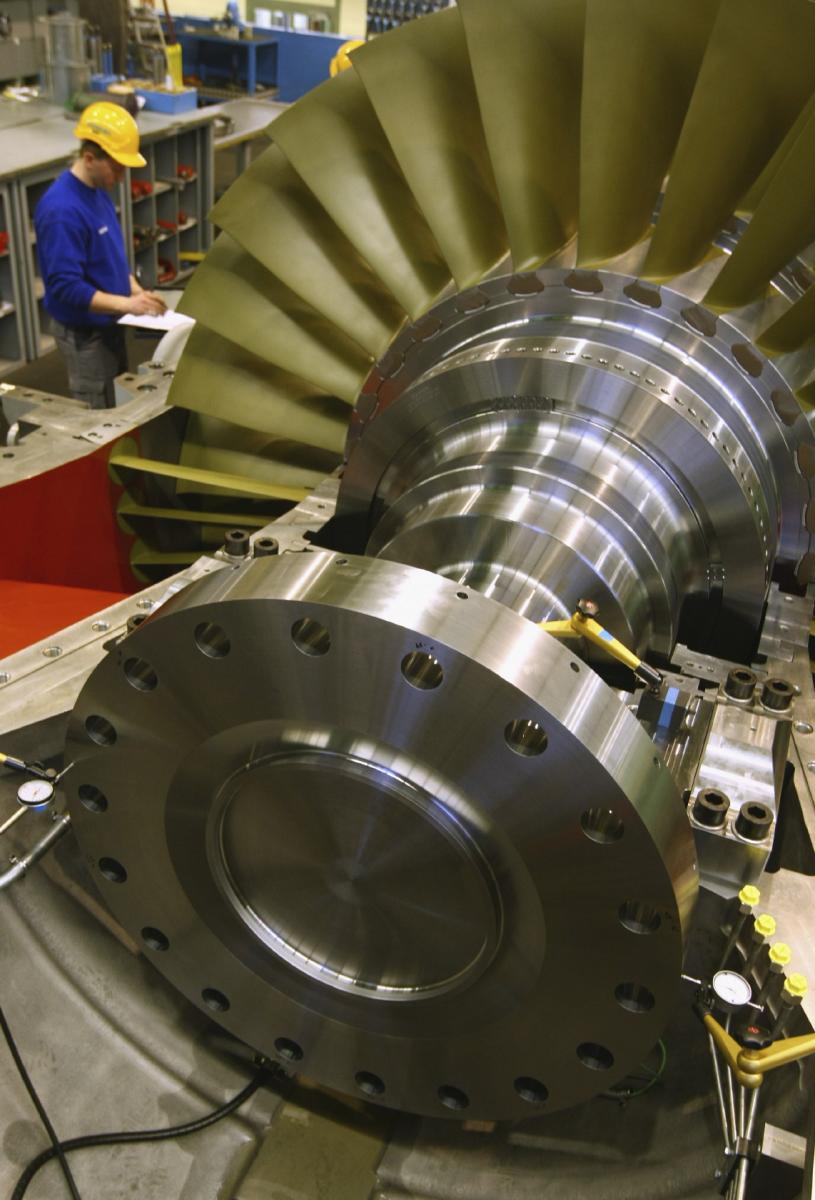

Meanwhile, German engineering company Siemens aims to be the world's first major industrial firm to attain a zero carbon footprint by 2030. It plans to invest around $112m to that end over the next three years. Anne-Marie Williams, senior analyst and engagement officer at ShareAction, which has partnered with RE100, says institutional investors including pension funds are increasingly open to the arguments for change.

“Facilitating these collaborative ventures is a key way to make progress,” she says. “In terms of engagement we feel that pension funds can perhaps be most influential by collaborating with other investors to form coalitions, e.g. Aiming for A, which submitted the BP and Shell resolutions earlier in the year.”

That Aiming for A campaign by 150 investors persuaded the oil and gas giants to agree to disclose risks associated with climate change. They are expected to issue reports and share their plans. “Also, we have spearheaded various initiatives around corporate lobbying by companies through their trade associations in the area of EU climate change policy and regulations around car emissions,” Williams says.

The insurance sector, led by companies such as Aviva, Old Mutual and Axa, is among those at the forefront of the move into low-carbon areas, probably because they are already seeing the results of climate change on their business, she adds.

Constructive engagement

However, ShareAction does not campaign for blanket divestment – except of thermal coal, which is the highest emitter of all the fossil fuels and is an industry with very poor prospects financially. The price of seaborne (exported) thermal coal has fallen dramatically from around $150 per tonne at its peak around 2011/12 to a current price of around $60 per tonne, with many companies driven bankrupt.

“We see a demand for general fossil fuel divestment from some of the charities in our investor network, as this is in alignment with their mission and ethics, but the general view we take is that at this stage there is value to be had from engaging with the oil and gas companies and effecting change in this way,” Williams says. This has to be monitored for effectiveness though, and divestment can perhaps be considered as a last resort if engagement fails, she adds. “As part of ShareAction’s Green Light campaign, we would definitely be recommending that pension funds reduce their exposure to high carbon areas, but just not divest them altogether, apart from thermal coal,” Williams says.

Farnworth hopes Paris will bring the clarity and drive that will make it impossible for companies to ignore green energy and other climate mitigation and adaptation measures. Ultimately, this should enable even power intensive industries such as mining and the oil and gas sector itself to adopt more renewable energy. “Many of them do so already with hydro schemes but we will see it become more widespread. Sometimes their needs are greater than what is available at the moment.

“One of the issues for renewables is that yes, prices are coming down but many players want policy certainty. Many INDCs [individual nationally determined contributions] for Paris specifically reference renewables as part of the delivery of carbon commitments, so it will be important to see good progress on that score.”

Joint action

The Prince of Wales Corporate Leaders Group (PWCLG), which represents 22 businesses around Europe including Tesco, Unilever, Jaguar Land Rover and Ferrovial, has urged EU and G20 finance ministers to do everything in their power to ensure a “smooth, just and rapid transition” to a low-carbon and climate-resilient economy.

The companies called on governments to deliver a robust deal in Paris and to translate it into domestic action. “The business community has made significant progress in understanding, reducing and reporting our impact on the climate, and is increasing investment in low carbon technologies and business models,” the PWCLG stated in an open letter at the end of October. “Global investment in clean energy, for example, reached $270bn last year, almost half of which was in developing countries,” the letter stated. But to sustain this growth, and the new jobs and investment it promises, effective national policies are required, the PWCLG wrote.

The companies asked ministers to:

-

Actively support an agreement that provides the clarity and certainty needed to invest in a low-carbon economy.

-

Ensure that the climate finance promised to developing countries is delivered and is used wisely.

-

Create the right fiscal environment that will accelerate private investment in low-carbon, resilient infrastructure and technology.

The PWCLG says that, for the Paris deal to be credible and durable, it should contain the following:

-

A long-term global emissions goal, such as peaking emissions as soon as possible and securing net zero emissions well before the end of the century.

-

Agreement to update and improve national mitigation commitments and adaptation plans every five years.

-

Clear transparency and accounting mechanisms.

Climate finance from the public sector can be used to leverage much larger flows of private capital by helping to de-risk investments into the industries and infrastructure of the future, the PWCLG said. Williams of ShareAction says it is also “really important” to look beyond Paris so that individual countries and companies move in that direction regardless of what is agreed.

Business role

Business will be key to the success of climate change action after the COP21 summit in Paris because governments will lack bite, according to research by GlobeScan, SustainAbility and the Climate Group. While a significant majority (92%) of experts are confident that the UN conference on climate change will result in a global agreement, only 32% believe it will have binding powers.

Confidence in the ability of governments to agree on a framework in Paris that would cut emissions in line with the 2ºC target is very low (4%) and the removal of subsidies for fossil fuels (82%) was rated the most effective economic instrument to contain global warming. Scientific institutions and civil society are seen as making the largest contribution to advancing action on climate change with more than half of respondents viewing their record positively.

The future contribution of national governments and business will be key to the implementation of the post-Paris framework, according to the survey. Eighty-six per cent of experts predict the private sector will play an “important” or “very important” role, and 90% of respondents believe the same for national governments. However, gaps between recent performance and future expectation mean that both institutions will have to step up their efforts.

The GlobeScan/SustainAbility Survey is one the longest-running expert surveys on sustainability-related topics of its kind. For the 2015 Climate Survey, expert stakeholders representing business, governments, NGOs, and academia shared their expectations for the COP21 meeting in Paris and provided insights about the role of various actors and climate change strategies post-2015.

Eric Whan, sustainability director at GlobeScan, says: “The convening parties, the UN and its national members, are not expected to deliver a result that the science says we need at Paris. Meanwhile, expectations are high that solutions will flow from the private sector almost as much as from national governments post-Paris, whatever the outcome. The pressure is on, and the companies that get this right will be the ones thriving 20 years from now.”

Opinions of expert stakeholders from 69 countries show that there has been a big turnover in perceived corporate leaders on climate change since Copenhagen in 2009, citing new champions including Unilever, Tesla, Ikea, Google, General Electric and Walmart. Aiste Brackley, research manager at SustainAbility, said corporate leadership was dominated by technology and consumer companies that had been at the forefront of investing in renewable energy and low carbon solutions – and were vocal about their initiatives on the global stage. “The landscape has significantly changed in recent years as only three companies – General Electric, Walmart and Toyota – that were included in the 2009 ranking made it onto the list this year.”

Apple google Siemens COP21 green tech green finance